With the overhaul of user accounts, we are proud to introduce a new feature: dashboards. As a registered user, you can now build a personal dashboard that allows you to track your favorite series and graphs. You can publicize your dashboard, so your colleagues, students or blog readers can follow the economic statistics you care about. You can create several dashboards and choose to keep them private or make them public.

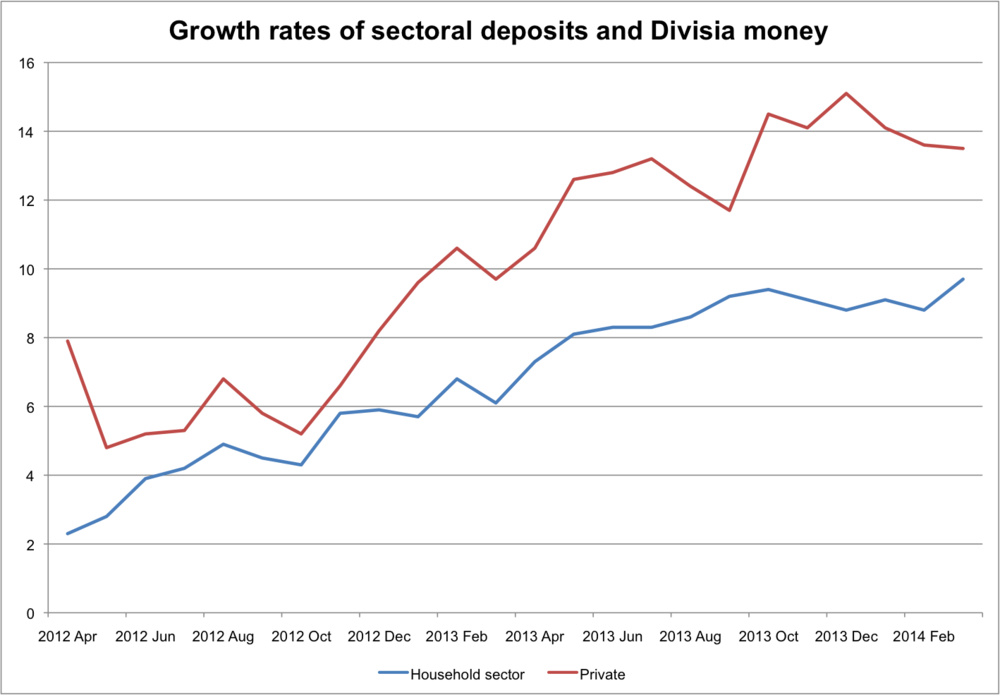

UK Divisia update

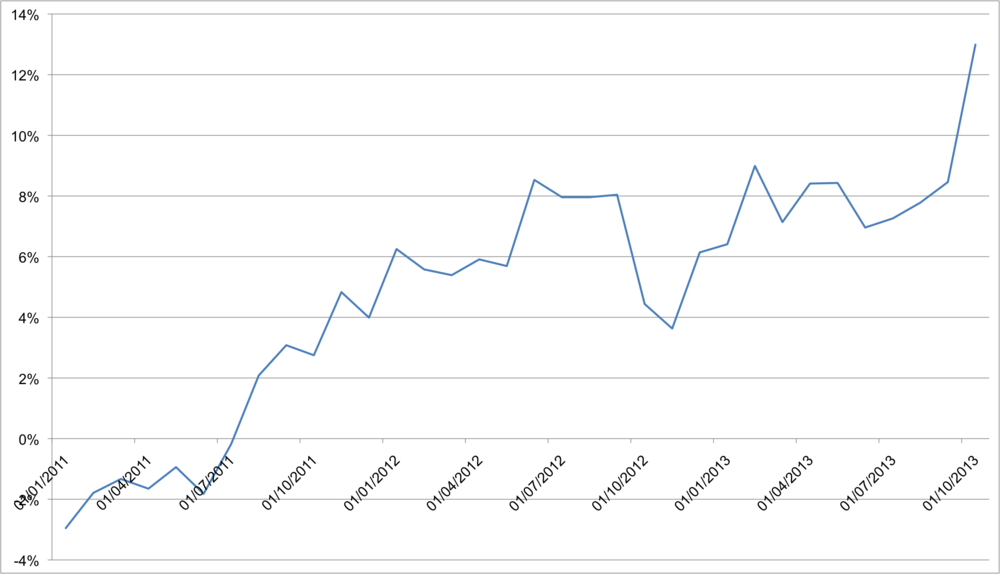

I'm not a massive fan of Divisia monetary aggregates, but I do think they are useful to look at. Here's the latest picture for the UK:

It comes from Table A6.1 in Bankstats.

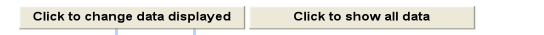

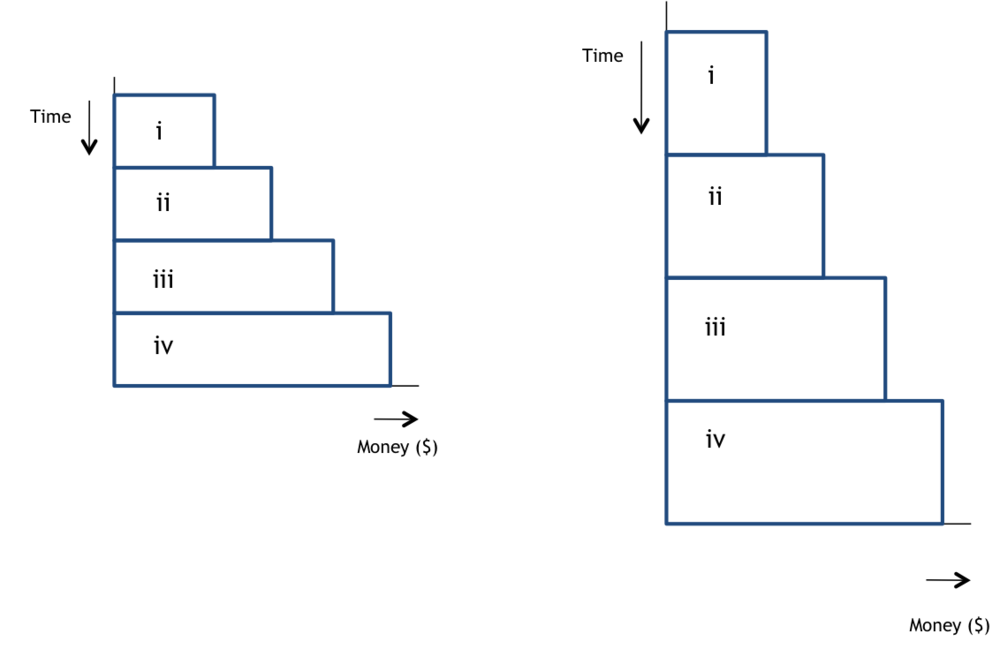

Average weekly earnings

It seems very hard to find data on UK nominal wages. Last year Britmouse wrote a post where he attempted to calculate nominal hourly wages relative to per capita NGDP. He says,

The ONS does not have an “official statistic” for nominal hourly wages, but they do publish some data in a spreadsheet in the Labour Market stats, which is updated quarterly.

This can be found by searching for "EARN08" at the ONS. I'm assuming that the reason nothing happens when I click on this is because I'm on a Mac?

Either way, I can't see the historic time series is. So I thought I'd just take a look at the simplest measure from the monthly Labour Market Statistics. The easiest way to find it is by clicking on the unemployment figure on the ONS front page. In the reference tables there's two options of interest:

- EARN01: Average Weekly Earnings

- EARN08: Distribution of Gross Hourly Earnings (as above)

Here's the AWE data:

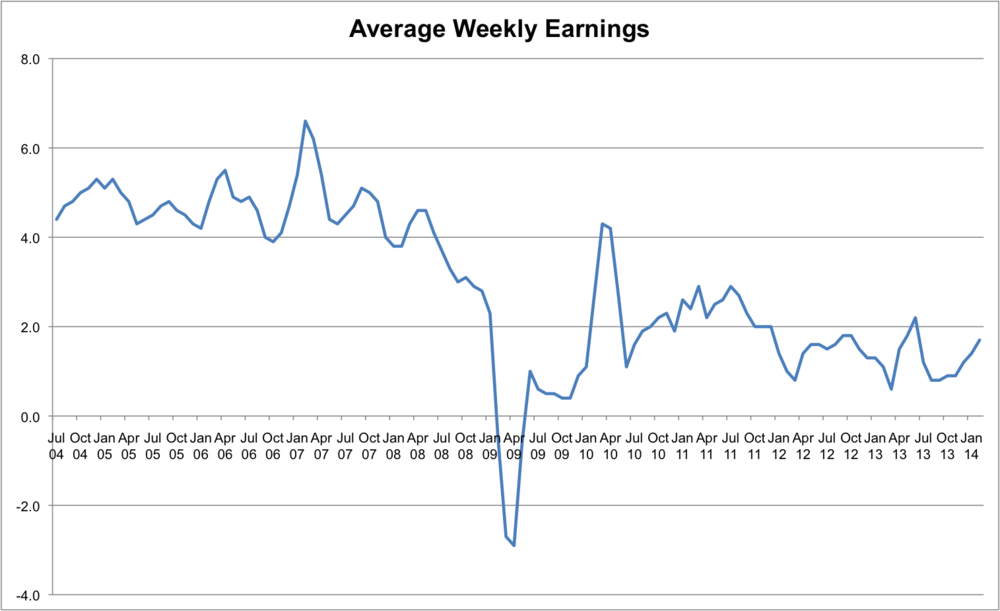

Roundaboutness

The term "roundaboutness" is often used in Austrian business cycle theory, and I'm not sure if it's a simple term being consistently applied, or something more complex. At the recent APEE meetings Nicholas Cachanosky presented a paper arguing that it isn't a mysterious concept (co authored with Peter Lewin), but I'm not sure I'm convinced. My basic understanding, stemming from Bohm-Bawerk is the following:

Roundaboutness = capital intensity.

Cachanosky & Lewin define roundaboutness as the "average period of production", and use net present value formulae and the concept of EVA to measure it. This is a great way to operationalise the concept, but is it "roundaboutness" that is straight forward, or their method?

One of the reasons I find Tyler Cowen's "Risk and Business Cycles" unsatisfying is because he doesn't really allow for different types of risk. In his treatment "risk" does all the work, and there's no need to talk about roundaboutness. I can't help feel that this fails to do justice to the Austrian story. Hence I am always wary of the following characterisation:

Roundaboutness = Time = Risk.

We can think of the interest rate as a measure of our time preference (or the ratio of the value of present goods to future goods), or a market generates risk assesment. Must they be the same thing? All else equal the longer the production process the greater the risk, but we can conceive of production plans that are risky but immediate (e.g. fashion) and those that are not so risky but distant (e.g. oil wells). In other words risk and roundaboutness are conceptually distinct.

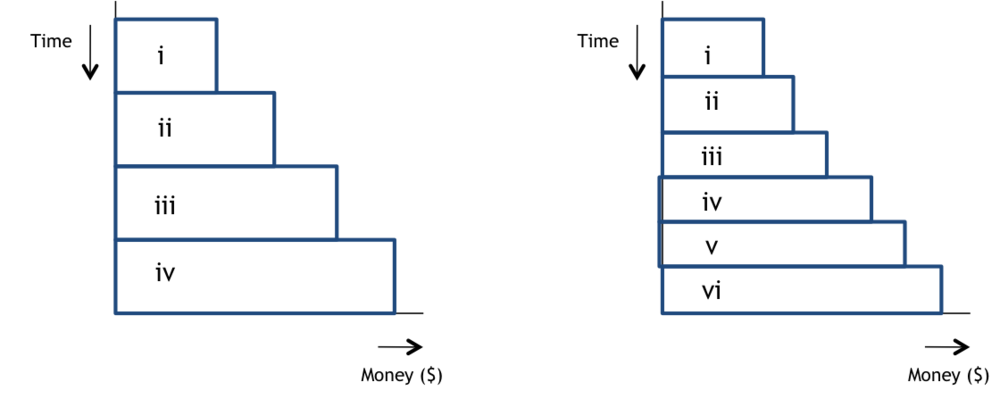

Consider a standard Hayekian triangle:

Now, whilst playing around with these diagrams can go too far, I think they're a good way to illustrate my point. Consider these two alternative ways of treating roundaboutness. Firstly, aa an increase in the production period:

Alternatively, roundaboutness could mean that there's more stages of production:

In the example above the final value of the consumer goods being generated is the same, but the value at all stages of production has increased. We could also show this where there's a change in the composition of the value from late stage to early stage:

And so on. It would be interesting to assign some possible applications to show that this is empirically relevant.

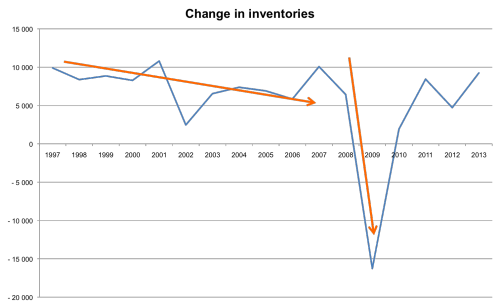

When sketching out these triangles I have in mind Lachmann's notion of reserve assets, which has recently been utilised by Robert Miller with his treatment of "buffer stocks" (here and here). It's hard to measure buffer stocks, and it's tempting to use inventories as a starting point. Here's what's happened to inventories in the UK over the last few years:

What we (sort of) see here is a steady decline in inventories from 1997 - 2007, which point to two things. Firstly, they get run down because excessive optimism means that entrepreneurs don't feel that they need them. And secondly, the utilisation of inventories as a means to generate unsustainable production (i.e. go beyond the PPF). Then during the crisis there's a dramatic reduction in inventories, and the "recovery" involves rebuilding. We need to be careful though, since inventories are just one source of buffer stock (and indeed one that is particularly close to consumer goods or final stage production). Some examples of buffer stocks include:

- Inventories

- Cash balances and other liquid assets

- Commodities (not only as aproduction input but also as a speculative hedge)

- Labour

- Any goods that are relatively less heterogeneuous that others and thus adept at fitting into an array of alternative production plans

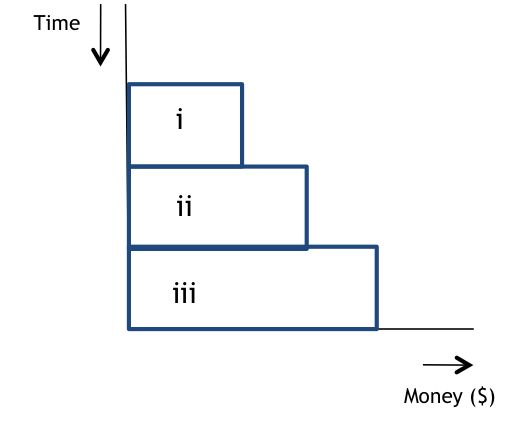

Finally, consider a Hayekian triangle and what's supposed to happen when interest rates fall. For simplicity, let's go use a 3-stage version.

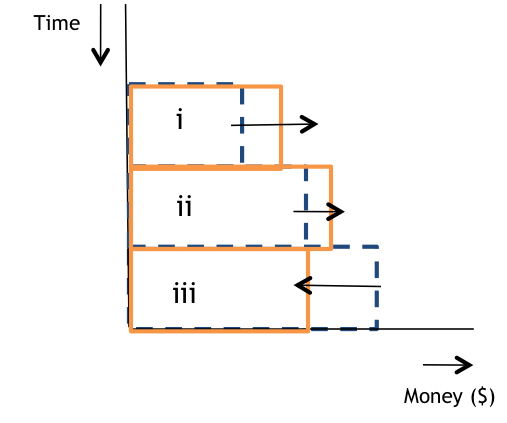

If lower interest rates induce entrepreneurs to move towards more roundabout methods we would expect resources to move from stage iii back to stage i. But stage iii is substantially larger than the early stages. Let's say we shift around 30% of the value in stage iii to stage ii, and likewise from stage ii to stage i. Here's (roughly) what we might see (original is dashed):

Is it not conceivable that the reduction in stage ii (as a result of activities being shifted to stage i) is offset by the shifted production from stage iii? In other words lower interest rates will cause unambiguous reductions in late stage production, increases in early stage production, but may also swell mid stage production? The stylised facts would be an increase in stage ii.

Gross Output makes The Wall Street Journal

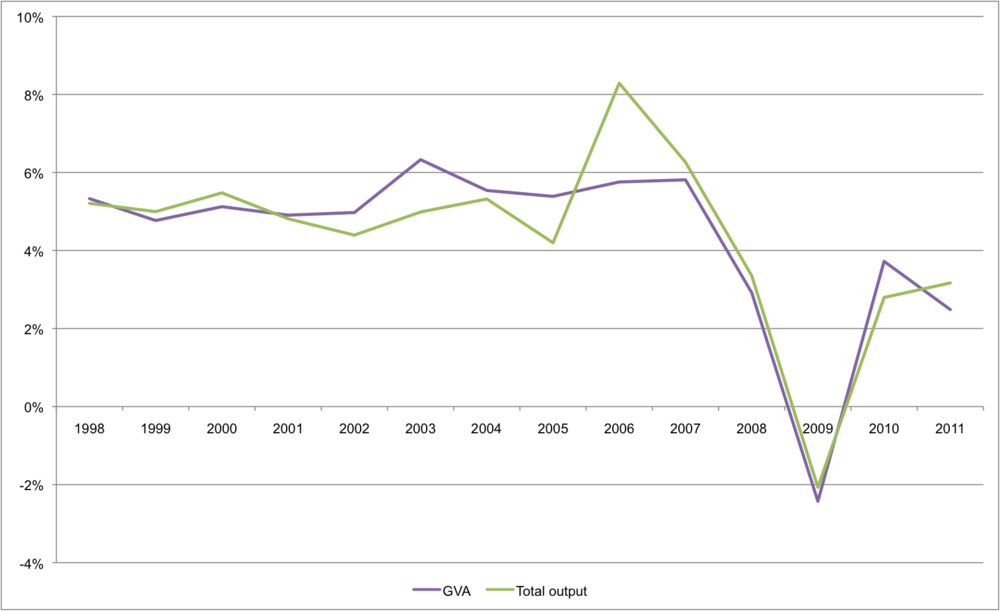

Mark Skousen has an opinion piece on 'Gross Output' in today's Wall Street Journal. Last week I presented estimates for the UK economy at the APEE conference in Las Vegas. You can view my presentation here. The chart below shows Gross Output for the UK economy (relative to GVA):

I plan to revise this shortly when the Supply and Use tables are published in July 2014, so this is only a rough treatment and I've not published the working paper. The data is released as separate tabs in an excel file but if anyboday would like the time series that I've created email me.

I plan to revise this shortly when the Supply and Use tables are published in July 2014, so this is only a rough treatment and I've not published the working paper. The data is released as separate tabs in an excel file but if anyboday would like the time series that I've created email me.

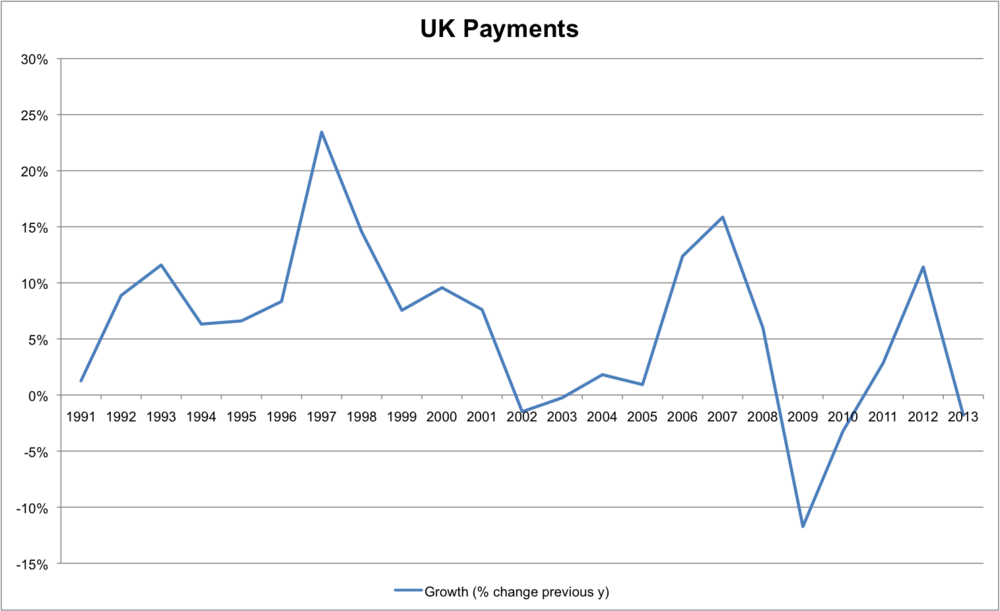

I also presented a measure of UK Payments. This also has data availability issues, with January 2010 figures simply missing from the data set. But here's what it looks like:

Bob Murphy on Hayek vs. Sraffa

I confess that I've never read the original sources of the Hayek vs. Sraffa debate, and suspect that it would be worthwile to do so. But I was never convinced that they would overturn or seriosuly challenge my existing understanding of Austrian business cycle theory. I recently read two accounts of the Hayek vs. Sraffa debate, and they validate this.

The first is Bob Murphy's "Multiple Interest Rates and Austrian Business Cycle Theory" (.pdf) He spends several pages outlining Sraffa's critique of Wicksell (and thus Hayek), several more pages discussing Hayek's response, and then even more on Lachmann. He essentially upholds Sraffa's point that in a world of multiple markets there is no singular natural rate of interest - "the" natural rate is a function of whichever good one arbitrarily decides to use as a numeraire. Murphy attempts to solve the problem of whether or not a natural interest rate exists in a barter economy by appealing to a concept of dynamic equilibrium. To be fair he credits Hayek with the basis for a dynamic, rather than static equilibrium construct, but he defines it as the following:

Austrians... should define a dynamic equilbrium construct where quantities, prices, resources, technologies, and even "spot" consumer preferences can evolve over time, but in a perfectly predictable manner

But in 'Prices and Production' Hayek cites "correct anticipation of future price movements" as one of the three criteria for neutral monetary policy (others being constant total income stream, and perfectly flexible prices, see p.131). This struck me as a solution in search of a problem.

In "The Clash of Economic Ideas" Larry White deals with the Hayek vs. Sraffa debate a lot more quickly. He says

Sraffa mistook Hayek's goal, which was not to replicate all the properties of a barter economy, but simply find a monetary policy that would not drive a wedge between savings and investment (p.92)

Isn't that the nub? When Austrians talk about "the" natural rate of interest it isn't because there is only one interest rate, but that there is one particular market that matters for intertemporal coodination. The market that bridges savings and investment. The market for loanable funds. Murphy's 40+ pages of text fail to mention "loanable funds" at all.

Sorry Pierro, but I still don't see what the fuss is about.

Bank of England on money creation

The Bank of England have published an interesting note on money creation. Given that Kaleidic publishes our own measure of the UK money supply, there is plenty that could be written about it. For now though, I just want to nip some of the crowing being done by MMTers. The way I understand the "money multiplier" is that there's a ratio between narrow and broad money. It's a bit like saying that there's a link between changes in human generated CO2 emissions and in average global temperatures. But identification of a ratio says nothing about causality. In the case of global warming, it seems that there is a large and vocal group claiming that the ratio (or correlation) is stable, predictable, and underpinned causaility. There's others who dispute this. There's probably even some who argue the causation runs the other way.

In the BoE report they say:

Another common misconception is that the central bank determines the quantity of loans and deposits in the economy by controlling the quantity of central bank money — the so-called ‘money multiplier’ approach.

central banks implement monetary policy by choosing a quantity of reserves. And, because there is assumed to be a constant ratio of broad money to base money, these reserves are then ‘multiplied up’ to a much greater change in bank loans and deposits

And then the killer argument:

While the money multiplier theory can be a useful way of introducing money and banking in economic textbooks, it is not an accurate description of how money is created in reality. Rather than controlling the quantity of reserves, central banks today typically implement monetary policy by setting the price of reserves — that is, interest rates

Obviously this depends on the textbook. In mine, I explain how central banks can affect the supply of money (through open market operations) or the demand for money (through interest rates) and the links between the two. I also mention that there is a ratio between broad money and narrow money. But I don't claim that the ratio is "constant". The term "multiplier" implies some sort of mechanistic causality. I think that's a strawman. I believe that considering the ratio between narrow and broad money, and the factors that cause that ratio to change, to be important.

I suspect that the reason the "money multiplier" is used so much is because it's descriptive and intuitive. The MMT crowd have a grain of truth in their critique. The challenge is to present an alternative that is more accurate but also just as usable. Whenever people criticise "textbook" economics, I wonder if they've actually read any. Or at least if they recognise that textbooks are starting points, and *not* the codification of everything we know and claim to be true.

Welcome to the great stagnation

Yesterday was the 11th quarterly meeting of Kaleidic Economics, and the topic was Tyler Cowen's 2011 thesis on "The Great Stagnation". There is a TED talk with Cowen here. The report is called "Welcome to the great stagnation". All of our reports are here.

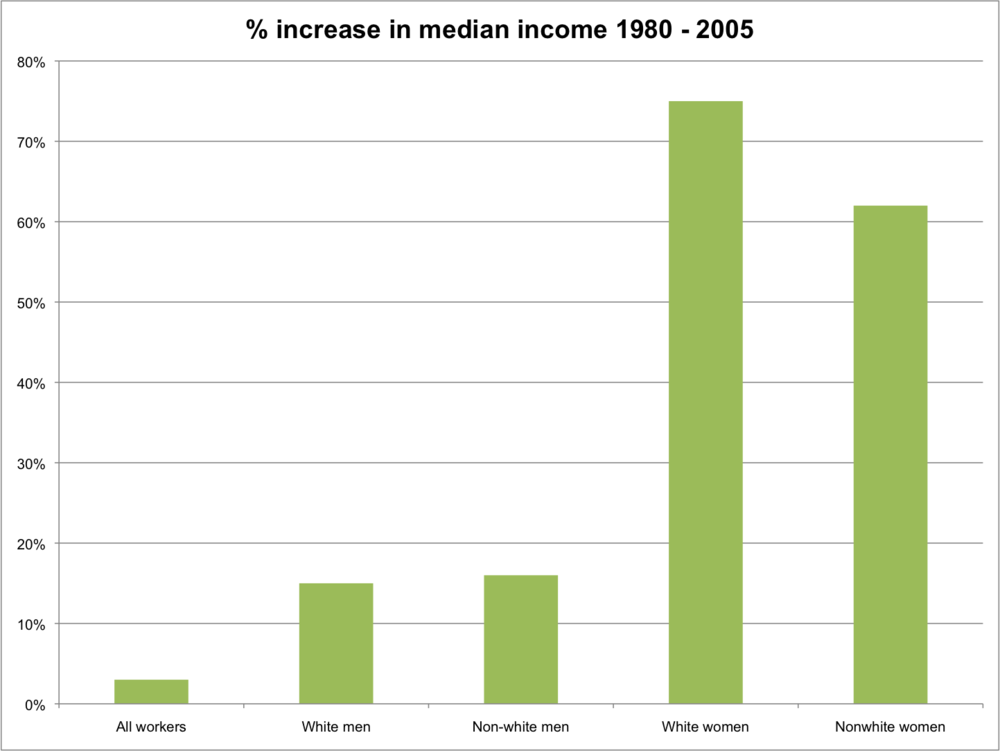

Here's a chart showing the breakdown of the increases in median incomes in the US, from 1980-2005. The data comes from Steven Landsburg. He shows how median income for all workers rose by just 3%, but that this masks what was happening within different groups. Since women represented an influx into the labour market, and their wages were typically below median, this dragged down the total. But every group rose.

To quote our report,

To quote our report,

time series data on median income gives the impression that we’re seeing what is happening to people’s incomes over time, but it doesn’t. It shows what happens to various income groups. This gives a misleading impression if the composition of those groups is changing. It’s like looking at Euston station during rush hour, and noticing that there are almost always 400 people on the concourse. This doesn’t mean that no one is getting home; it just means that for every train that departs, more people arrive. Immigration will continue to top up the lower income group, such that median incomes appear stagnant. But this is a positive demonstration of the dynamic effects of the economy. It’s a strength, not a weakness

Overall though we are sympathetic to the view that the rate of growth in incomes, productivity, and technological innovation has slowed. This doesn't necessarily mean that living standards are falling, since we are getting better at learning how to consume the technologies that we do have. We can be utility optimists but output pessimists.

Here's our introduction:

This report confronts Cowen’s argument, and considers how it relates to some specific questions relating to the UK economy. In particular, why has productivity nose-dived since the recession? And are lower growth rates, and lower interest rates, part of a “new normal”?

Which battle are we fighting?

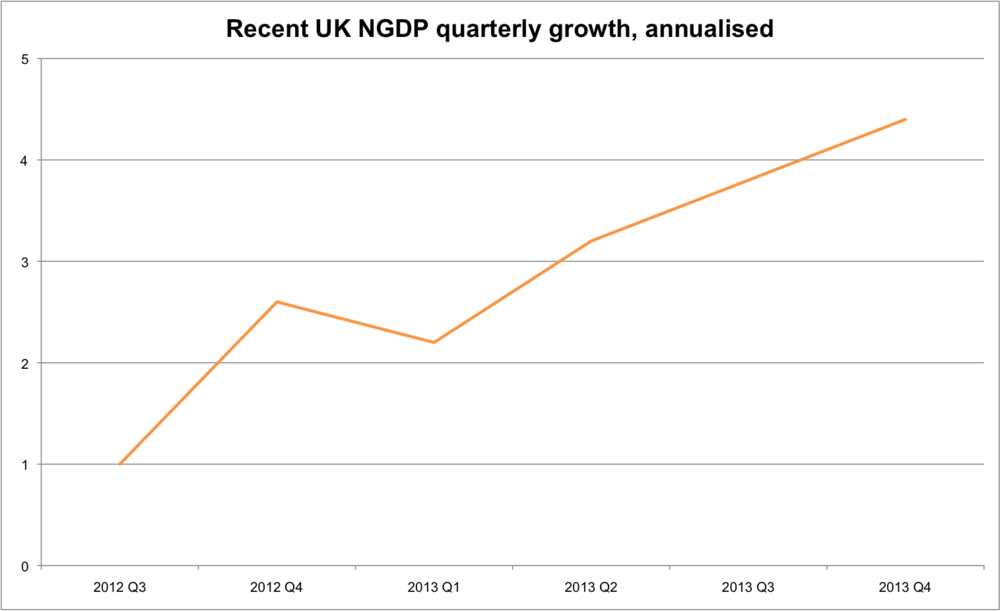

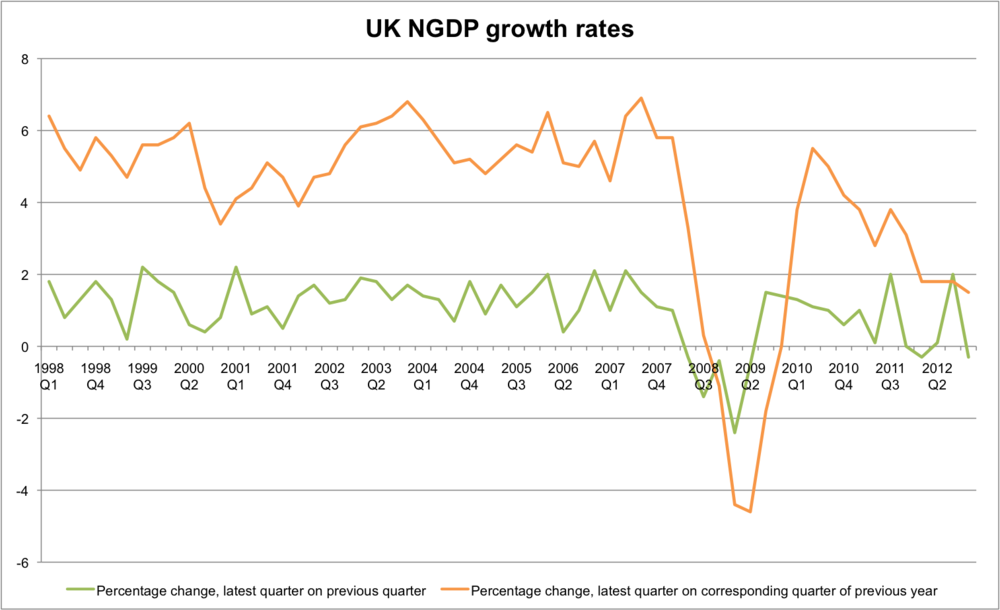

The second estimate of GDP came out recently, and with it the first estimate of NGDP for Q4 2013 (see Britmouse here, see our guide to UK national accounts here). Once again, the growth rate is strong. Here's the quarterly rate:

Here's a chart showing the quarterly rate, compared to the same quarter of the previous year (series code IHYO):

I am incredibly sympathetic to market monetarism and feel that they have been consistently ahead of the curve. But identifyng a shortfall of NGDP growth expectations as being the primary reason for the recession, does not necessarily mean that a shortfall of AD is the current problem. Obviously, the charts above leave us some way off where NGDP would be absent the recession. But as with most Austrians, I don't believe that this counterfactual is plausible. Even the most monetarist of market monetarists would agree that an NGDP growth rate of 500% is suboptimal, even if anticipated. Austrians think that the same applies (albeit to a much lesser degree) with one of 5%.

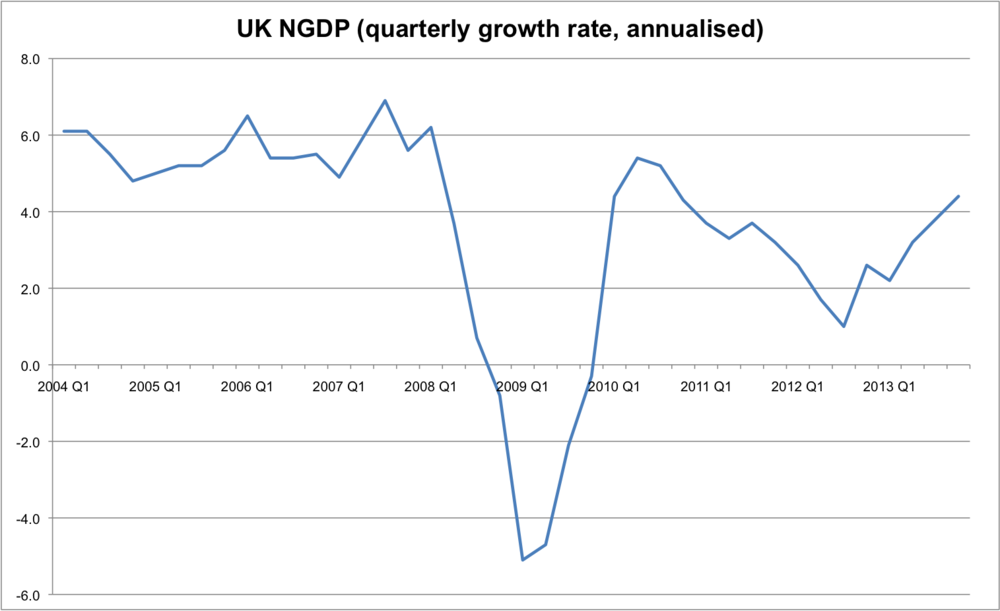

The chart below takes a longer look at what's been happening to NGDP (also QoQ of previous year):  Clearly, the focus on inflation targets rather than collapsing NGDP was a major oversight by the Bank of England. We'd all be better off if monetary policy was more neutral during 2008, rather than being highly contractionary. What I'm less sure of, however, is the argument that monetary policy is too tight right now. The stable door is open. The horse has bolted. Optimal monetary policy would ignore past errors and guide NGDP expectations towards a sustainable growth path. A level target means that bygones are not bygones when shocks occur, for a given target. But since part of the debate is what an optimal NGDP level target would be, it's ok for market monetarists to be wary of loose monetary policy.

Clearly, the focus on inflation targets rather than collapsing NGDP was a major oversight by the Bank of England. We'd all be better off if monetary policy was more neutral during 2008, rather than being highly contractionary. What I'm less sure of, however, is the argument that monetary policy is too tight right now. The stable door is open. The horse has bolted. Optimal monetary policy would ignore past errors and guide NGDP expectations towards a sustainable growth path. A level target means that bygones are not bygones when shocks occur, for a given target. But since part of the debate is what an optimal NGDP level target would be, it's ok for market monetarists to be wary of loose monetary policy.

P.S. This post is focused on the UK economy. The argument that monetary policy is too tight in the Eurozone is a lot more convincing, and it's plausible that deflationary pressures may become a problem for the UK economy too. If it does, I will change my position.

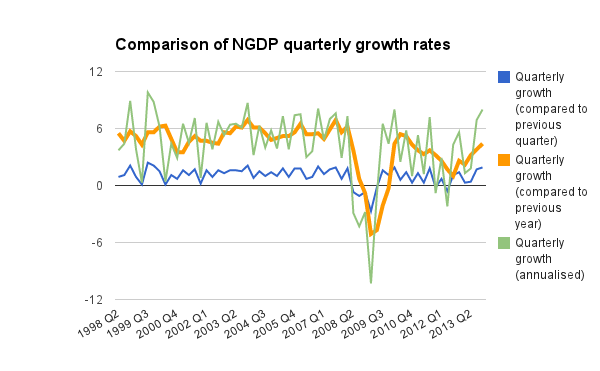

P.P.S I shouldn't have used the term "annualised" in the charts above. I was confused because I'd just been reading Britmouse's analysis, and he likes to annualise the data. There's two reasons why I prefer to look at the quarterly growth rate, relative to the previous year. Firstly, it is publicly available. When the ONS release the National Accounts you can look at Table A2 and there it is. There's no need to do any calculations. This is preferable because it's easier, and more credible. And secondly, it seems more indicative of what's going on. The chart below compares three quarterly growth rates:

- Quarterly growth compared to previous quarter (IHYN) BLUE

- Quarterly growth compared to same quarter of previous year (IHYO) ORANGE

- Quarterly growth annualised (my calculations) GREEN

OK, I've cheated and put my favoured one in a thicker line. But if you want a snapshot of NGDP, I believe this is the least erratic, and most useful measure. It also avoids the fact that I've probably made an error calculating the annualised version...

What's happening with business investment?

On January 1st the FT published a survey of several economics commentators. It's an interesting read and worth spending some time on. One thing that many people mentioned was the role of business investment. The general consensus seems to be that business investment is expected to pick up again in mid 2014, and this is necessary for a sustained recovery.

I've been attempting to update the "private investment" indicator that Kaleidic Economics publishes, and trying to come to terms with changes in how the ONS report the data. I'm a bit confused, and will look at it again later. But in the meantime I thought I would just focus on business investment alone.

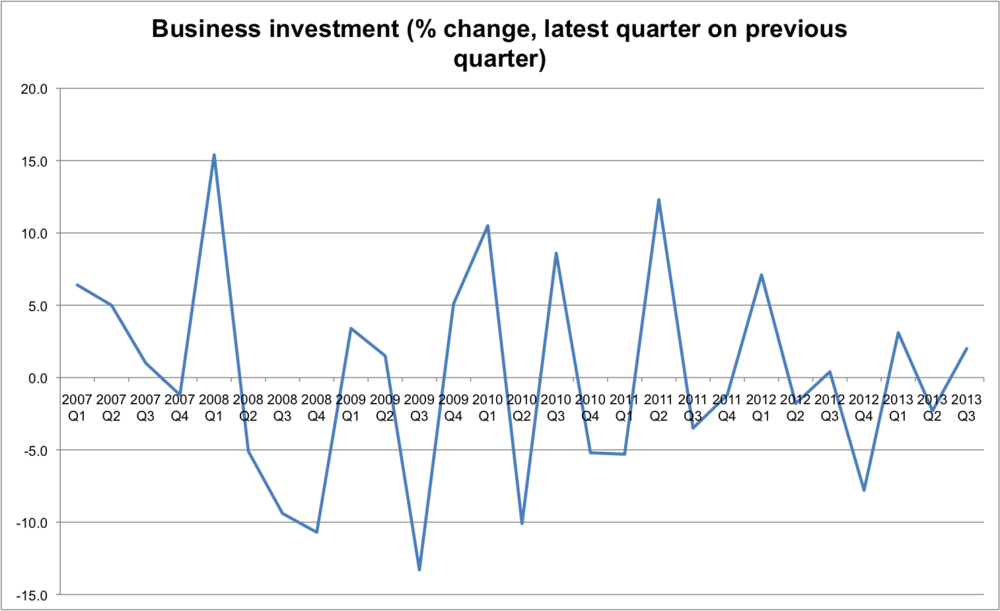

Firstly, consider the quarterly growth rate:

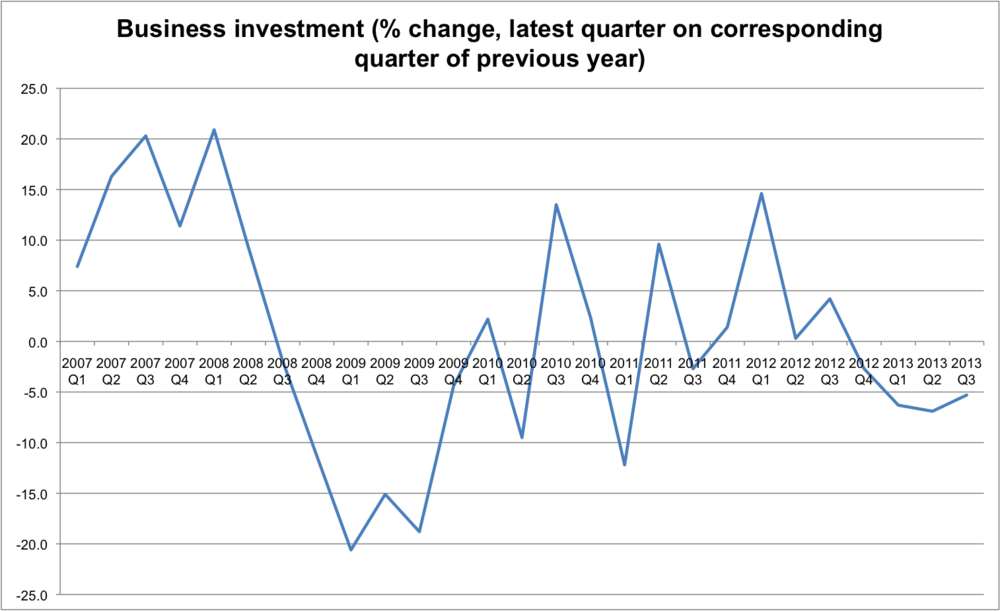

Business investment is volatile, and to get a clearer picture we can instead look at the quarterly growth rate compared to the same quarter of the previous year:

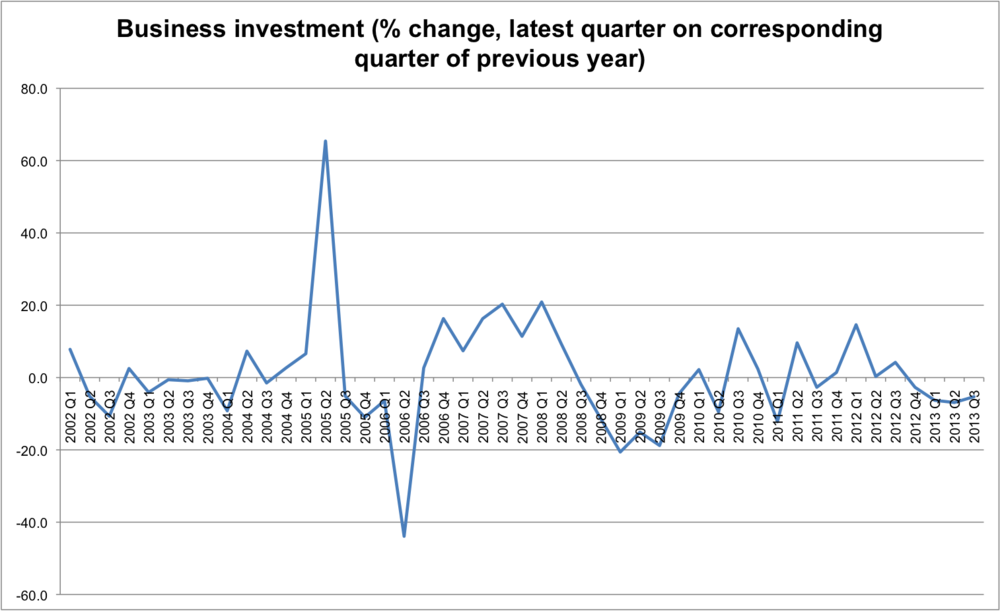

The dramatic decline in 2009 is evident, as is a spluttering rebound with recent figures being very weak. Perhaps the slight upturn we see in Q3 2013, together with more optimistic GDP forecasts for early 2014, will result in increased business investment. But what constitutes a normal rate? The chart below takes it back to 2002.

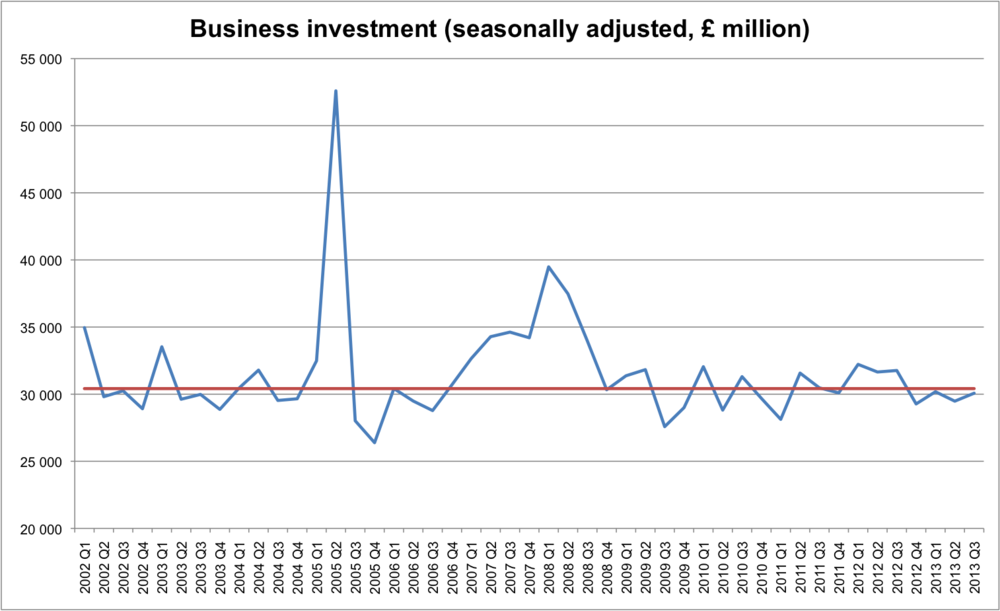

It isn't clear what an appropriate growth rate should be, for a balanced economy. Indeed the chart below shows the absolute numbers, with the red line denoting the median level. So what are we waiting for?

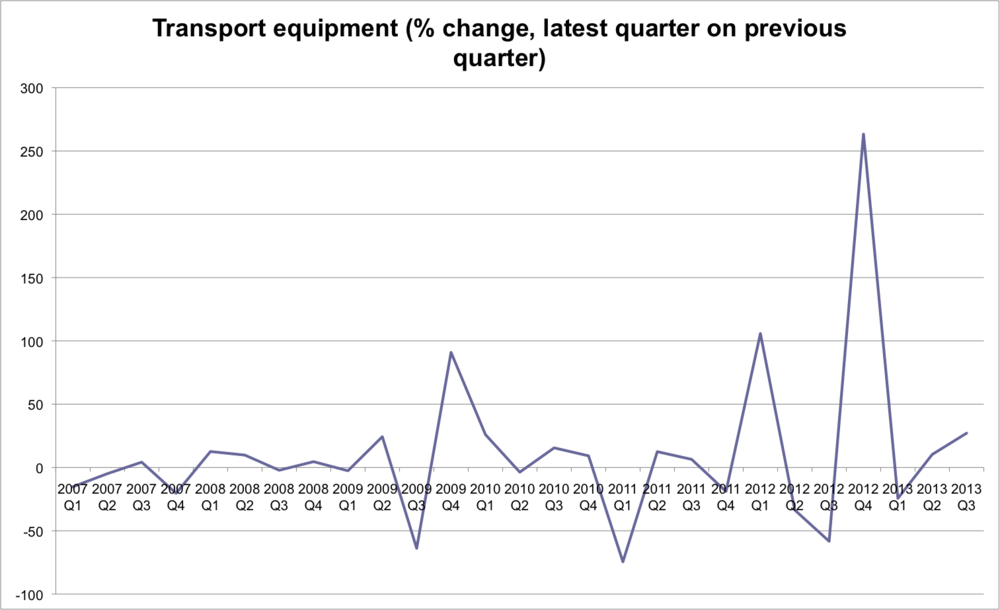

Transport equipment volatility

The chart below shows investment in "Transport equipment" from 2007 to Q3 2013. It is a lot more volatile than it has been previously, with an especially large increase in Q4 2012.

Here's the raw numbers, showing that the spike in growth rate is the result of being at a low base. This is because of a large decline from Q4 2010 to Q1 2011.

Does anyone know the detail as to what was driving this?

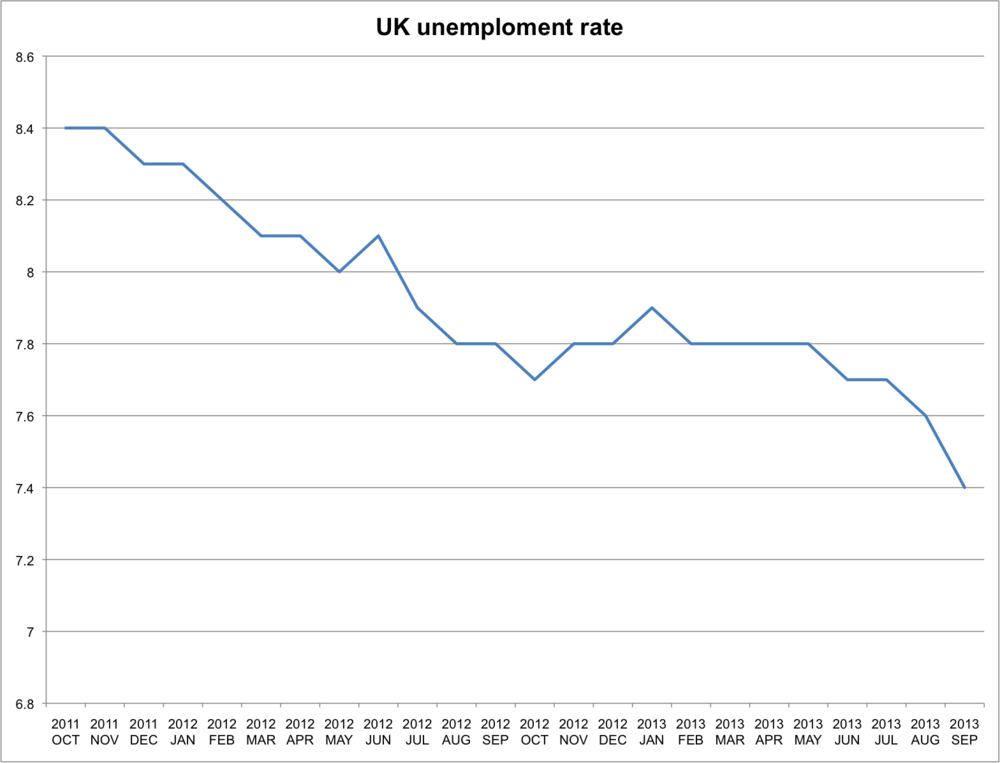

UK unemployment

There's lots of talk that UK unemployment is falling faster than expected, and the Bank of England have brought forward their forecast that it will first fall below 7% from 2016 to 2014. As the chart below shows the rate has steadily fallen since late 2011.

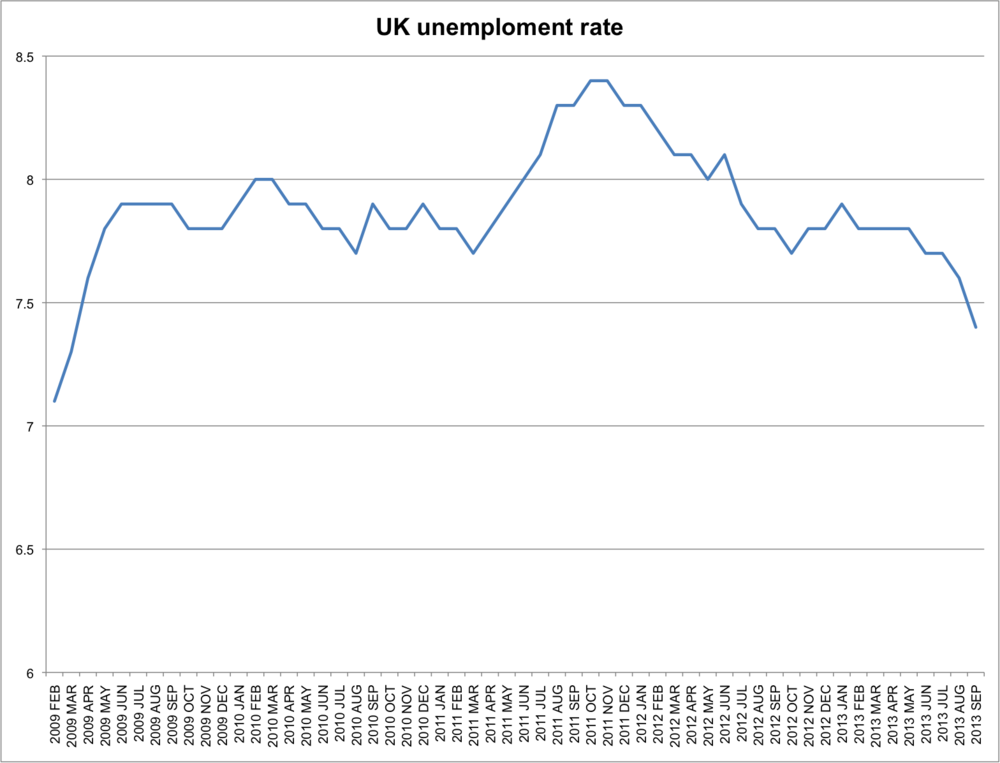

But this is also a nice exercise in the importance of time frame. Here's the same data from February 2009 (i.e. the month in which it went above 7% for the first time)

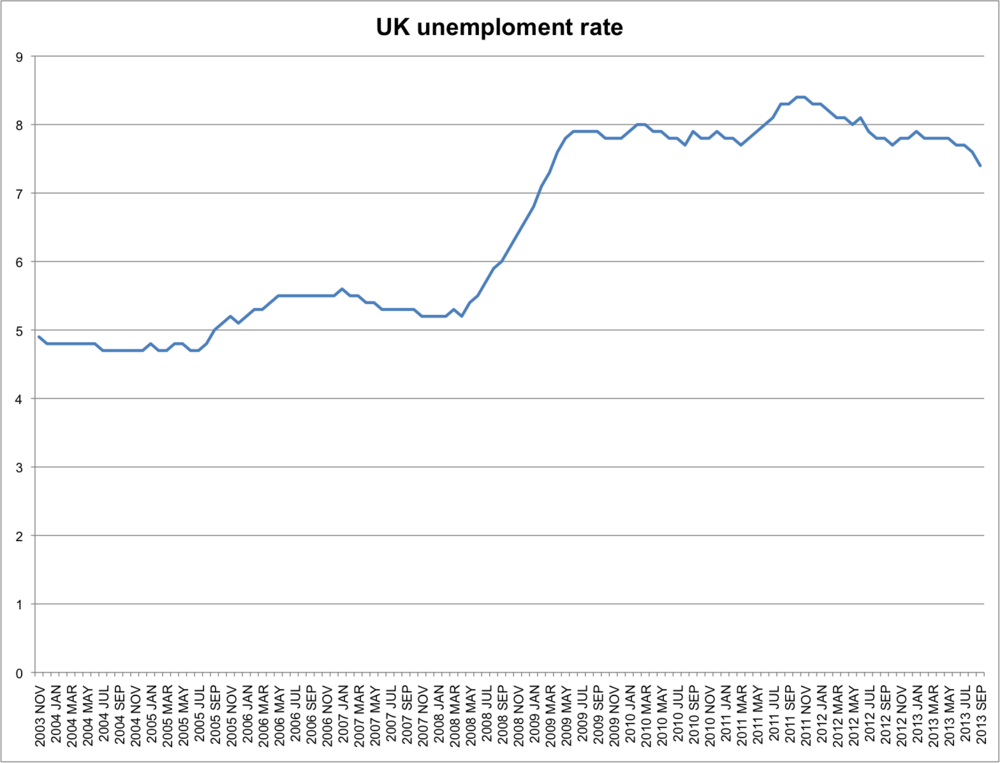

And here it is going back the last decade

I'm using UK unemployment rate aged 16+ (series code MGSX)

MA takes off

A belated update of MA reveals that the money supply in October jumped to a growth rate of 12.99% (compared to October 2012). The growth rate had been consistently between 7% and 8% since April 2013. This gives further evidence that the UK economy is picking up speed, and perhaps too much. More details in the data section.

(For some reason Google Drive seems unable to show charts, so I've copy and pasted the data into Excel and saved this as an image.)

The Yakiniku recovery

Last week saw the 9th quarterly meeting of Kaleidic Economics, and the topic was low growth scenarios, with a particular focus on Japan.

In the paper we discuss the conflicting debates about the extent to which "the lost decade" is a myth, and whether this is a result of too much, or too little, policy response. The table below shows some typical literature, and interestingly demonstrates that even within the scame school of thought, there are differences of opinion.

|

|

Policy response |

||

|

Loose |

Tight |

||

|

Lost decade? |

Myth |

(i) ? |

(ii) Kelly (2011) Krugman (2013)? |

|

Reality |

(iii) Powell (2002) Shostak (2013) |

(iv) Krugman (1998) Greenwood (2006) |

|

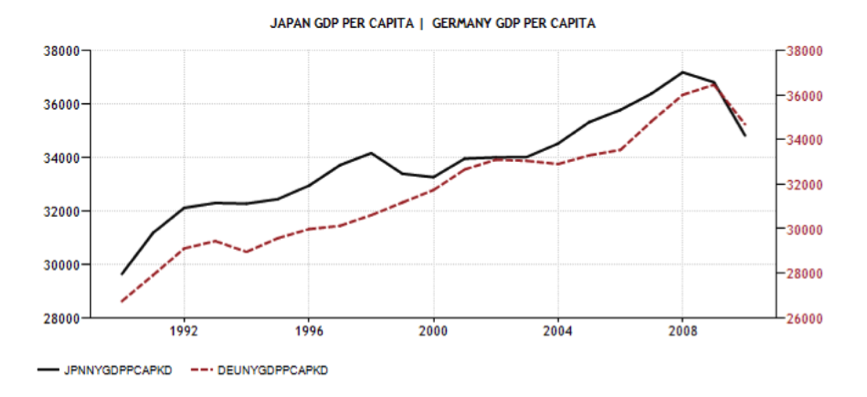

Readers may also be interested in the chart showing Japanese GDP per capita relative to Germany, throughout the so-called lost decade [via http://www.tradingeconomics.com/]:

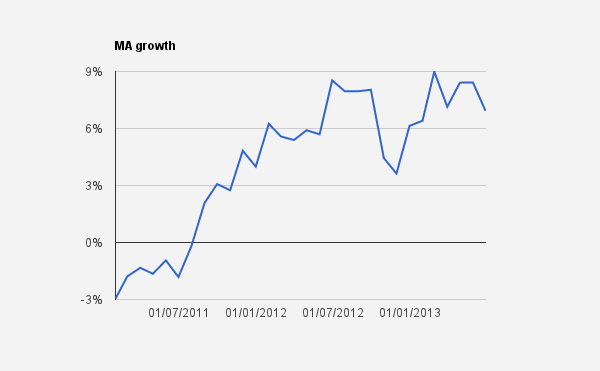

MA continues to grow

We've just updated our measure of the money supply, MA. It has demonstrated more than 6% growth per month (compared to previous year) for the whole of 2013, and was at 6.93% for June. For an interactive chart and details on compilation see our data section.

Kelly Evans on NGDP prediction markets

Here's a CNBC clip of Kelly Evans (no relation) talking about a prediction market in NGDP. (H/T Lars Christensen).

New prediction market for 2014 Q1 NGDP

Last year we opened a few prediction markets relating to NGDP figures, and I was pleased to see that over 90 trades were made. They were very much a work in progress and since then we've been trying to think what the most useful types of question are. Here's an interesting post that outlines some of the key considerations:

- How far apart should the contracts be spaced? 3 months, 6 months, 12 months?

- Should the contract payout be proportional the level of NGDP or the rate of change of NGDP in some period?

- How far out should the contracts start? What are the most important expectations? Expectations about NGDP 6 months out? 12? 24?

- What BEA data should the contracts be based on? Advance, Primary, Secondary or Final NGDP estimates?

Our latest question is as follows:

It's important to explain it a little. There are several ways in which we can look at NGDP. Using the final estimate of 2012 Q4 we see the following (using Tables A1 and C1 - for our guide on UK National Accounts see here):

Level path (YBEU): 110.8

Percentage change, quarter on previous quarter (IHYN): -0.3

Percentage change, quarter on corresponding quarter of previous year (IHYO): 1.5

Absolute amount (YBHA): £388,350m

The reason we are interested in NGDP is because we are interested in NGDP level targeting. As Lars Christensen has pointed out in relation to our previous prediction market, it's the level of GDP that matters. But as Britmouse added, the level gets routinely rebased. (Update 28/6/13: for example, in a previous market we asked what the level of NGDP for 2012 would be. The second estimate (released May 2013) said 110.0, but the final estimate (released June 2013) said 105.2. The reason is that for the final release the base year changed from 2009 to 2010). That's not the only problem. From a policy perspective, we may be interested in how actual NGDP relates to, say, a 5% NGDP level target. But we'd then need to choose a starting point, and compile shadow statistics that project a 5% path on top. It would be possible to project 5% NGDP growth from the height of the boom onwards, and then operate a prediction market in terms of the absolute amount of NGDP with those projections in mind. However the reason we've decided against this is that (i) it involves an arbitrary choice of target growth and starting points; (ii) it would be hard to relate those values to the figures released by the ONS. In other words we want to focus squarley on the official ONS figures.

There is a widespread discussion about GDP growth and we want to tap into that. If you ask someone what's happening to GDP they're not going to be thinking in terms of levels (relative to 2009, or some other base year) or indeed the absolute amount. It's growth rates that are in the news. So the real decision is which growth rate - should we compare it to the previous quarter, or to the same quarter of the previous year? Let's look at the data:

The headline growth rate of GDP is in terms of quarter on quarter change, which in our case is the green line. The orange line shows the percentage change based on the same quarter of the previous year. To be clear, the Q4 2012 figure in the chart differs because the green line is relative to Q3 2012, whilst the orange line is relative to Q4 2011. Given how I've argued that we want to tie into the public awareness of growth rates it'd make sense to focus on quarter on quarter change (green). But it's not very interesting. The change relative to corresponding quarter (orange) tells a far richer story, with NGDP growing by around 5% from 1998 - 2007, collapsing to less than -4% in 2009, rebounding in early 2010, and then embarking on a downward trend. Critically this seems a closer fit to thinking in terms of an overall 5% GDP level target. To be sure we're not looking at the level path, so we can't tell from the chart above what NGDP "should" be now in order to get back to the 5% path. But if you want to use 5% as your benchmark you can easily see whether we're "catching up" or "falling behind". And indeed if you advocate a different NGDP level target (for example 2%) then you can still get meaningful insights from a prediction market focused on growth rates.

So we're very much asking a question that is imperfect. But I want to stress that the purpose of the prediction market is to generate interest in NGDP expectations. It is *not* to serve as a policy tool. If you wanted to adopt an NGDP level target you'd need a far richer suite of institutional designs. You'd need the government to release NGDP indexed bonds. You'd need to agree on a level target. Etc. This prediction markets is intended as a very small step to contribute to the wider public debate. So focusing on an annual growth rate is seen as the most modest option. We can't switch debate from real GDP QoQ growth rates to nominal GDP level path relative to an arbitrary growth rate in one step.

The reason we're using the primary release is because this is when there's most public interest in the figure, since it provides the first look. Of course it is likely to be revised in subsequent releases, but it makes sense to only focus on one. In addition the ONS intend to start including NGDP figures in their primary release. We've decided to exploit this happy coincidence.

There are several different ways in which we could ask the question. Previously we used a multiple choice answers to deliver a real time estimate of the probability of each possible outcome. Here were the options:

As it turns out, the second estimate (released February 27th) gave a figure of 109.8. But the third estimate (released March 27th) revised this to 110. The problem isn't just ambiguity about which release would be used, it is because if the "true" value falls close to the border between different options, you lose a significant part of the predictive power. It places a higher burden on the question design (and indeed the question designer!). With that in mind this time the question works in a slightly different way. We set an opening price of £50 and this is scaled by 0.1 to imply an expected growth rate of 5.0%. Traders can either buy or sell shares relating to that probability value, and in doing so move the market.

It remains to be seen whether there's enough interest in this market to warrant a separate one for every quarter. I suspect that we will open up a market for 2015 Q1, for 2016 Q1, etc. We'll respond to market demand. For now though jump in and start trading. If the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee incorporate the insights of this prediction market as a complement to their current sources of information, decision making would be improved. Indeed if they set a rule by which they would alter make interest rate decisions such that this market stays at 5%, we'd be getting somewhere...

Guide to using the UK National Accounts

Update (March 2016): The ONS have re-designed their website and whilst it may make it easier to navigate, the links below are no longer valid. I will update soon.

In the past I've struggled a great deal trying to navigate the ONS website, and although it's improving I thought I'd write a brief guide to understanding the National Accounts. Although GDP is measured on a quarterly basis, "new" figures are released each month. This page is for people that see a figure being reported in the news, and want to know where it's come from. In addition, I hope to raise awareness of Nominal GDP, and how to find this in the official data.

The table below shows a stable link for the three different releases. By finding the current month, you will see wherabouts the ONS are in the cycle. The Preliminary estimates tend to get more headlines because they are the first indication of the shape of the economy. So April, July, October and January tend to be when GDP figures are in the headlines. But these are subject to revision, and it's quite possible that what gets announced as a "recession" turns out not to be one.

Also, don't forget that even the "final estimate" is subject to revisions. For example, when the Final estimate of the Q2 data is released in September we tend to compare it to the Second estimate, released in August. But the September release may also adjust the data for previous quarters, such as Q1.

| Calender of GDP releases | Preliminary Estimate (First Estimate) |

Second Estimate | Quarterly National Accounts (Final Estimate) |

| Q1 (Jan, Feb, Mar) |

April | May | June |

| Q2 (Apr, May, Jun) |

July | August | September |

| Q3 (Jul, Aug, Sep) |

October | November | December |

| Q4 (Oct, Nov, Dec) |

January | February | March |

When you click on the link you will have two options:

- If you want to view the data:

- Statistical bulletin > Download PDF

- If you want to download the data (or see data over a longer period):

- Reference Tables > Quarterly National Accounts Data Table

The preliminary estimate doesn't contain the same amount of information as the second and third. I believe that this will soon change, but for now:

- Preliminary estimate

- See Table B1 - the second column from the right shows "Gross Domestic Product at market prices"

- The headline figure that gets reported in the news is the quarterly growth rate compared to the previous quarter - series code IHYQ

- Second estimate and third estimate

- See Table A1 - this shows annual levels, quartely levels, annual change, quarterly change (compared to previous quarter), and quarterly change (compared to previous year). The headline figure has the same series code as in the preliminary estimate - IHYQ. The third column is showing Real GDP (i.e. GDP at market prices).

- We can also see estimates for NGDP (i.e. GDP at current prices) in the first column.

Note that:

NGDP = Real GDP + GDP Deflator

You can also do this for annual figures (YoY change)

IHYO = IHYR + IHYU

IHYM = IHYP + IHYS

Or quarterly figures (QoQ change)

IHYN = IHYQ + IHYT

- For full details of NGDP see Table C1. This shows "Gross Domestic Product at market prices" but measured in current prices.

- The comparable figure to the headline GDP figure is the "percentage change , latest quarter on previous quarter" - series code IHYN

- The figure that ties in best to NGDP targets is "percentage change , latest quarter on corresponding quarter of previous year" - series code IHYO

- Table A2 can be useful because it shows absolute levels - if you want to verify the growth rates you can calculate them yourself from this data

- Table F shows Gross Fixed Capital Formation which is essentially investment

For more, here's a guide by the Chief Economist of the ONS.

An alternative way to find annual NGDP data is to look at "Money GDP" from HM Treasury, which goes back to 1955.

Exercise

On April 25th 2013 The Guardian wrote:

George Osborne has welcomed news that Britain's economy expanded by a stronger-than-expected 0.3% in the first quarter of 2013, avoiding a triple-dip recession.

As the first estimate from the Office for National Statistics showed that a healthy performance from the services sector helped GDP growth to beat the 0.1% expected by City pundits, the chancellor said it was evidence that the coalition's policies were helping to "build an economy fit for the future".

Using the information in this post you should be able to go to download that very release, and see where the reported 0.3% figure comes from.

2013 NGDPLT Summit: Copenhagen

The 8th Quarterly Meeting will be held in Copenhagen and take a detailed look at the theoretical desirability and political feasibility of NGDP level targeting being adopted in the UK. It is an attempt to bring together a broad group of people interested in Market Monetarism.

Here's the agenda:

Monday May 13th

12:30pm: Meet for lunch

Then: Tour of Danske Bank

Then: Visit to CEPOS for discussion

- Why free market economists should take NGDP targets seriously

- Some Austrian considerations for NGDP targets

- What would Hayek say about NGDP targets?

- Towards a market in NGDP futures

- Political strategy - how should we be positioned in the political debate

- An actual strategy for implementing reforms to UK monetary policy

Then: Dinner

Tuesday May 14th

Depart.

Attendance is strictly by invitation only.

Some public sector net investment scenarios...

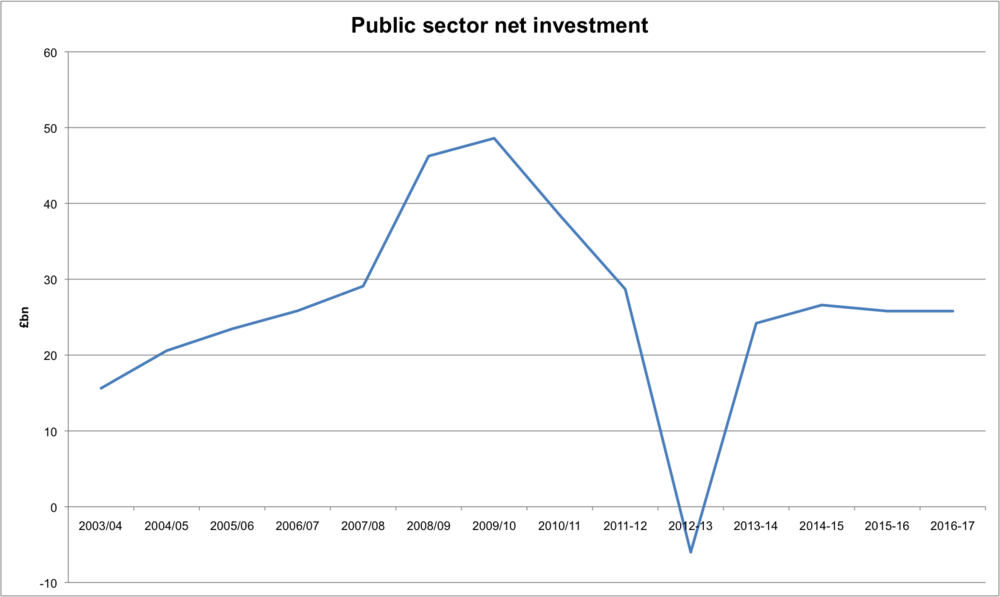

In a previous post on government spending I looked at public sector net investment from 2003/04 until 2011/12. Here's an updated version using the Budget 2013 forecasts through 2016/17.

The decline in 2012/13 is immediately apparent, but it's important to see that by 2014/15 spending is forecast to return to it's 2007 level. The debate is really about the the severity of the contraction since the 2010 general election, the extent to which that was an inevitable consequence of a 2009 fiscal stimulus, and the one off factors (such as transfer of Royal Mail assets) that distort the figures. What strikes me though is that I don't know any economists that would advise the government to do the above.

The decline in 2012/13 is immediately apparent, but it's important to see that by 2014/15 spending is forecast to return to it's 2007 level. The debate is really about the the severity of the contraction since the 2010 general election, the extent to which that was an inevitable consequence of a 2009 fiscal stimulus, and the one off factors (such as transfer of Royal Mail assets) that distort the figures. What strikes me though is that I don't know any economists that would advise the government to do the above.

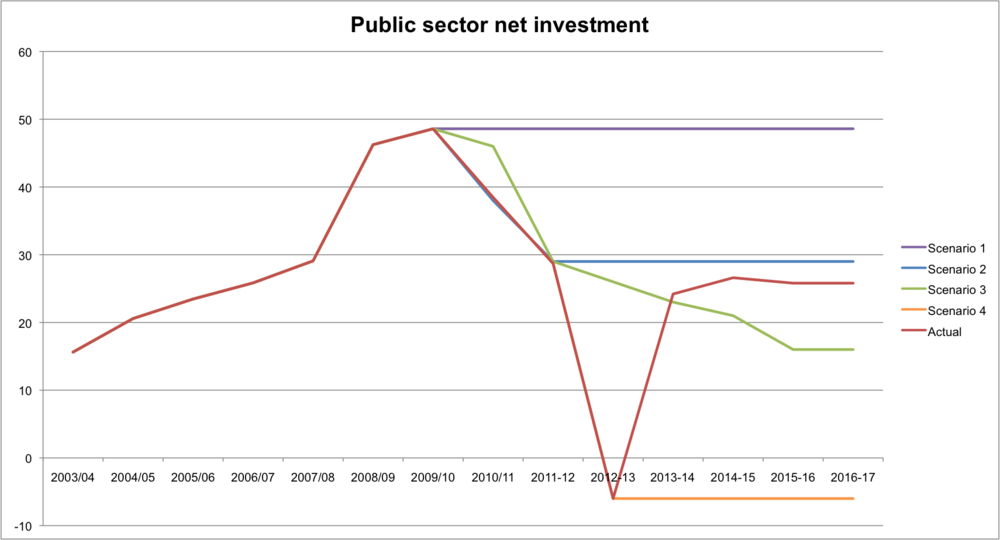

The chart below includes 4 scenarios:

- The purple line (scenario 1) is the arch Keynesian "keep on spending until the economy recovers and to hell with the debt!" It's what I suspect many Keynesians believe, albeit are very reluctant to admit to.

- The blue line (scenario 2) treats the 2009 stimulus as a temporary injection, and maintains investment at its pre stimulus levels

- The green line (scenario 3) acknowledges that the 2008 - 2011 spike put public debt on a new course, and therefore mirrors the rise in order to steadily return to 2004 levels

- The orange line (scenario 4) is an ultra austerian desire to shrink the state, allow depreciation to eat up the existing capital stock, and flat line with negative net investment

- The red line (actual) is taken from the March 2013 Budget.

I'd be really interested to know various preference orderings. My intuition is that scenario 3 would be preferred to the actual by both sides of the debate. Indeed one would think that the serious debate would be between scenarios 2 and 3.

Source: 2003/04 - 2010/11 from PSF1 of the Public Sector Finances.