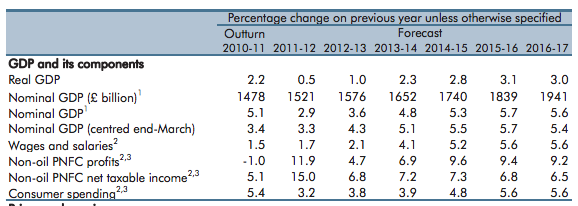

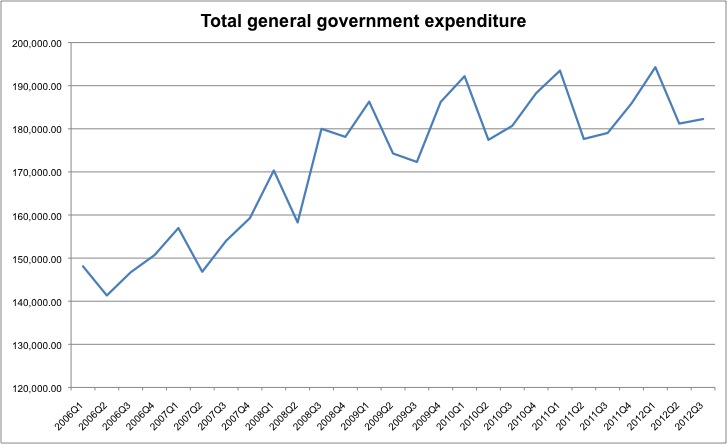

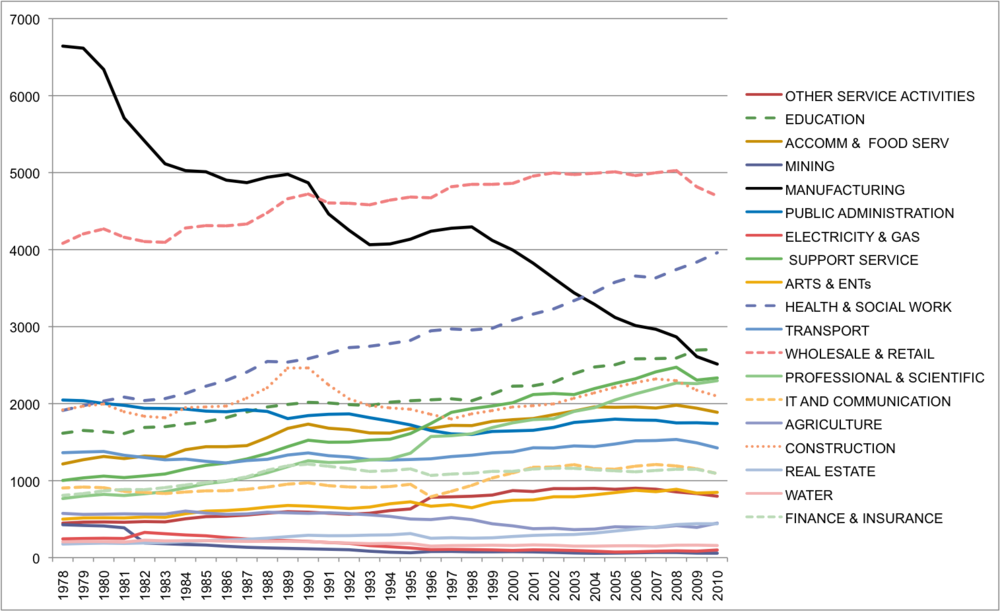

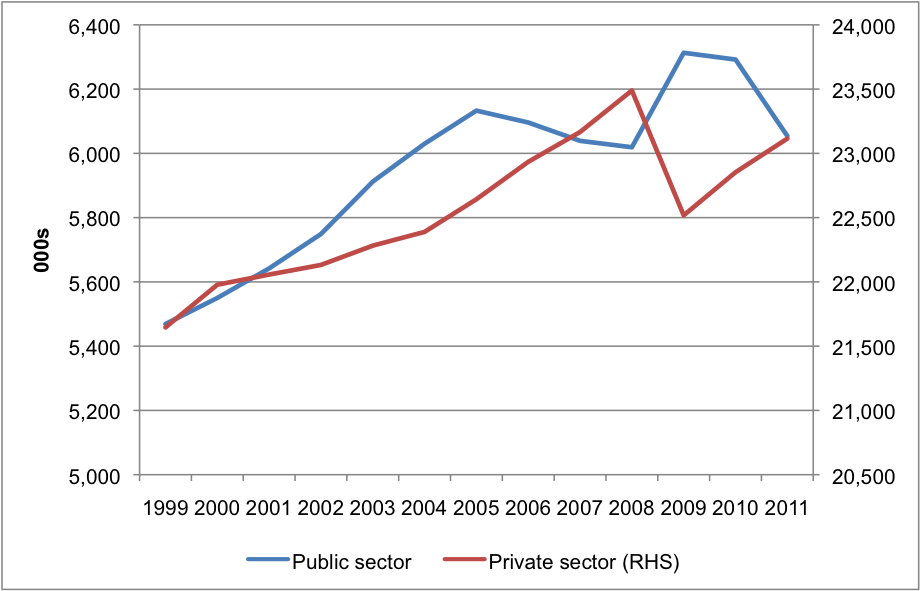

I'm not an expert on this data but I find spending figures as a proportion of GDP deeply flawed (since they're driven by implausible growth forecasts). So I've been trying to navigate the ONS website to find some raw figures on government investment. Here's two ways to look at it:

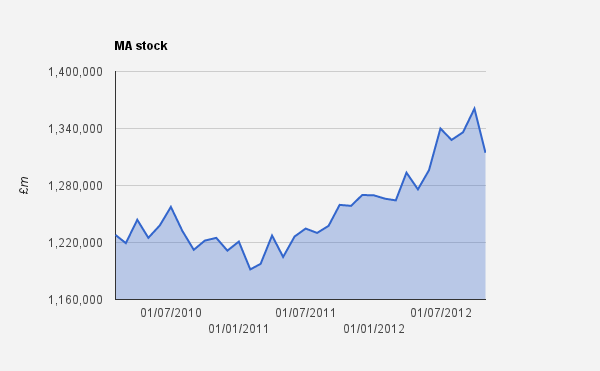

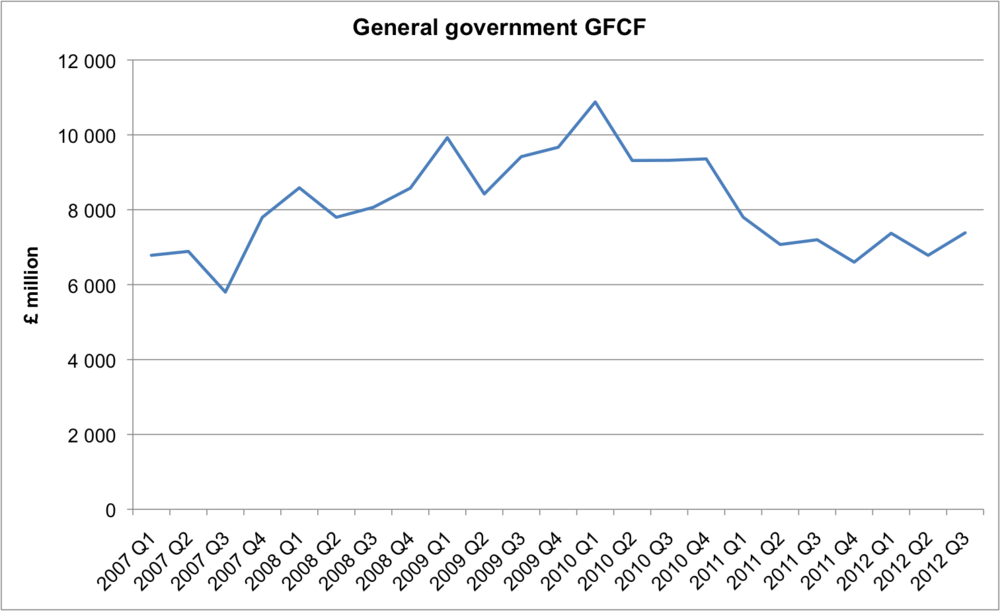

- General Government GFCF - Table F of the national accounts (see here for a guide to using the national accounts, and here for our comparison of General government and private GFCF).

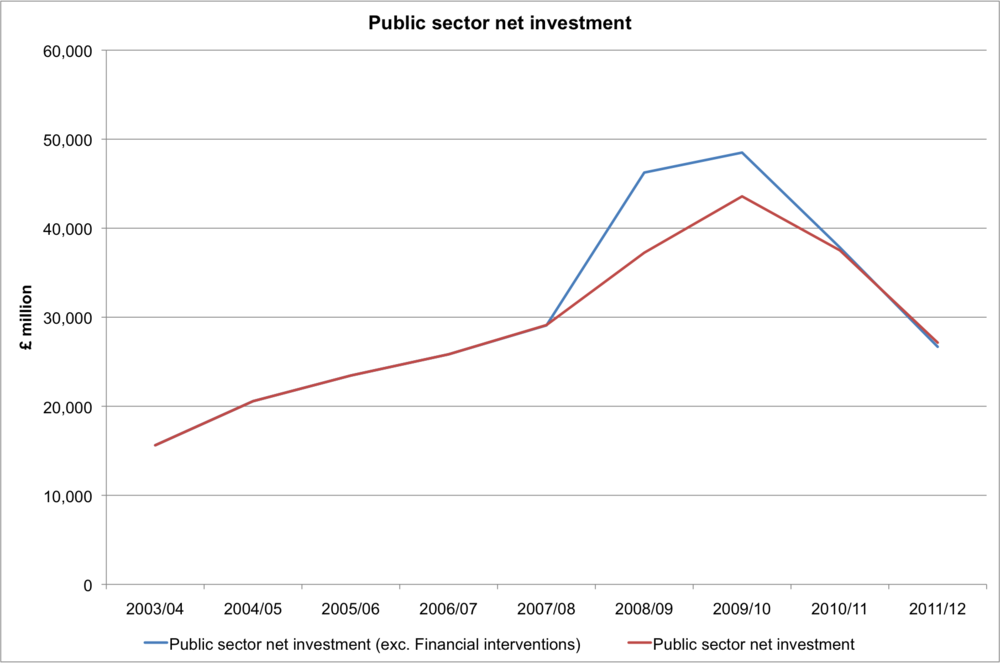

- Public Sector Net Invesment (excluding financial interventions) - Table PSFN1 of the Public Sector Finances (see here for Sep 2012). If anyone knows how to download these figures in Excel, please let me know!

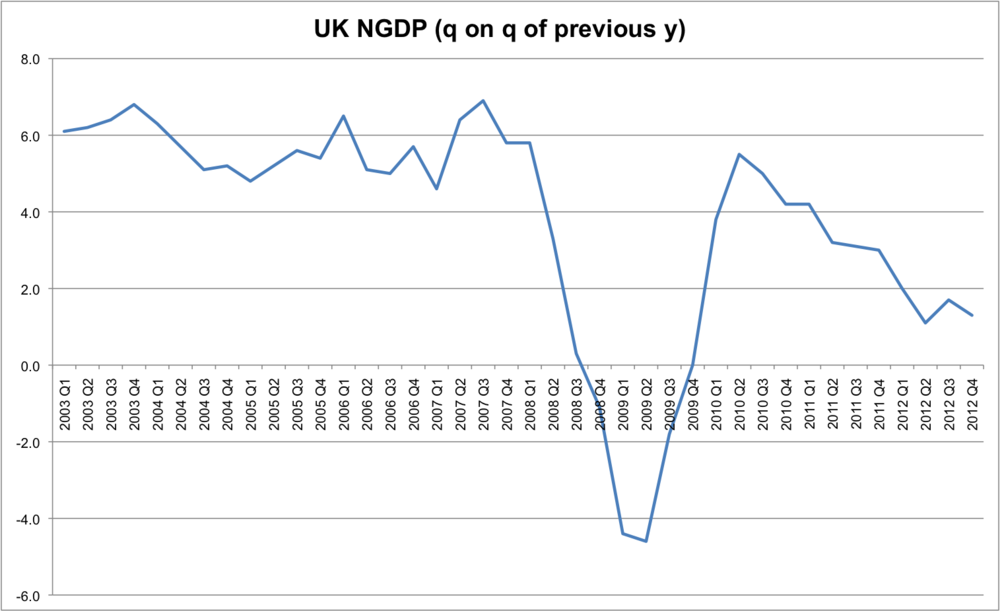

The point I'd make is that the dramatic cuts seen made by the coalition government (i.e. from 2010 onwards) are only "cuts" relative to the time of the fiscal stimulus of 2009. When Keynesian economists advocate fiscal stimulus they are arguing for temporary deficit financed spending. Therefore by definition a stimulus will be "withdrawn" at some point in the future. The argument against a stimulus is that it may be withdrawn prior to the economy recovering. If you say "don't withdraw it until the economy recovers" then to what extent is that a temporary programme? And both sides would acknowledge that all else equal, the higher the existing debt level the more dangerous a "permanent" fiscal stimulus is. Let's not also forget that part of the 2009 fiscal stimulus brought forward capital spending due to take place in 2010-2012. It's like me asking to be paid 2 weeks early and then in a fortnight time complaining about having a pay cut.

I'd love someone to point out errors in my interpretation and use of the data (in particular I'd love to find a stable link to these indicators). I just think that although analysis like this is far more sophisticated than my own, to only start looking at what's happened since 2009/10 is deeply misleading. Keynesians - you got the stimulus you asked for. If you want another one I'm willing to debate that. But you can't simply pretend that the first one never happened!