Last year we opened a few prediction markets relating to NGDP figures, and I was pleased to see that over 90 trades were made. They were very much a work in progress and since then we've been trying to think what the most useful types of question are. Here's an interesting post that outlines some of the key considerations:

- How far apart should the contracts be spaced? 3 months, 6 months, 12 months?

- Should the contract payout be proportional the level of NGDP or the rate of change of NGDP in some period?

- How far out should the contracts start? What are the most important expectations? Expectations about NGDP 6 months out? 12? 24?

- What BEA data should the contracts be based on? Advance, Primary, Secondary or Final NGDP estimates?

Our latest question is as follows:

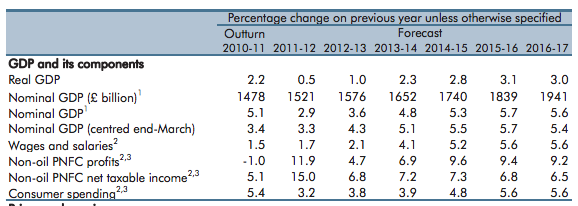

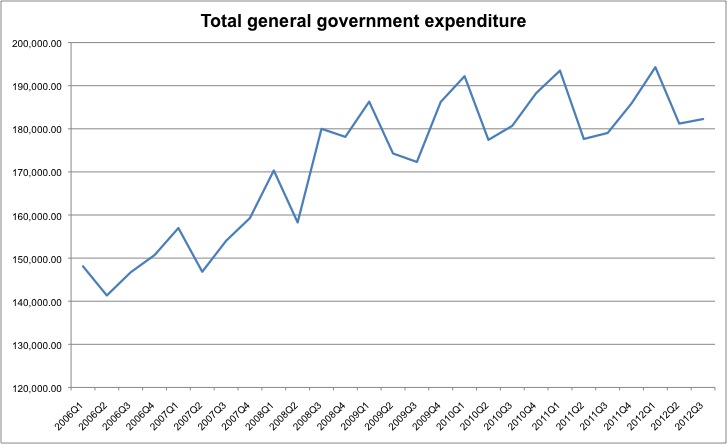

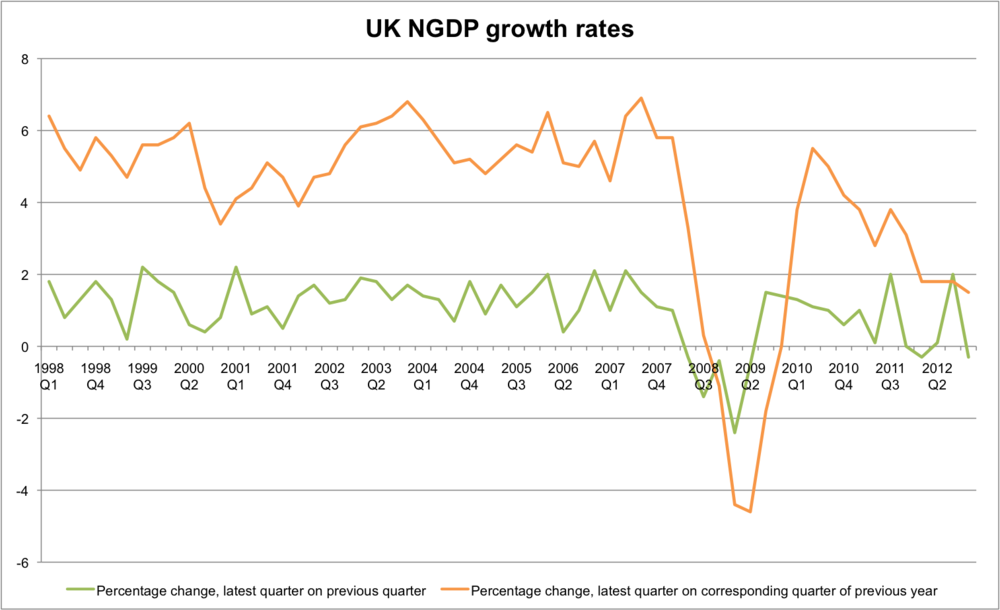

It's important to explain it a little. There are several ways in which we can look at NGDP. Using the final estimate of 2012 Q4 we see the following (using Tables A1 and C1 - for our guide on UK National Accounts see here):

Level path (YBEU): 110.8

Percentage change, quarter on previous quarter (IHYN): -0.3

Percentage change, quarter on corresponding quarter of previous year (IHYO): 1.5

Absolute amount (YBHA): £388,350m

The reason we are interested in NGDP is because we are interested in NGDP level targeting. As Lars Christensen has pointed out in relation to our previous prediction market, it's the level of GDP that matters. But as Britmouse added, the level gets routinely rebased. (Update 28/6/13: for example, in a previous market we asked what the level of NGDP for 2012 would be. The second estimate (released May 2013) said 110.0, but the final estimate (released June 2013) said 105.2. The reason is that for the final release the base year changed from 2009 to 2010). That's not the only problem. From a policy perspective, we may be interested in how actual NGDP relates to, say, a 5% NGDP level target. But we'd then need to choose a starting point, and compile shadow statistics that project a 5% path on top. It would be possible to project 5% NGDP growth from the height of the boom onwards, and then operate a prediction market in terms of the absolute amount of NGDP with those projections in mind. However the reason we've decided against this is that (i) it involves an arbitrary choice of target growth and starting points; (ii) it would be hard to relate those values to the figures released by the ONS. In other words we want to focus squarley on the official ONS figures.

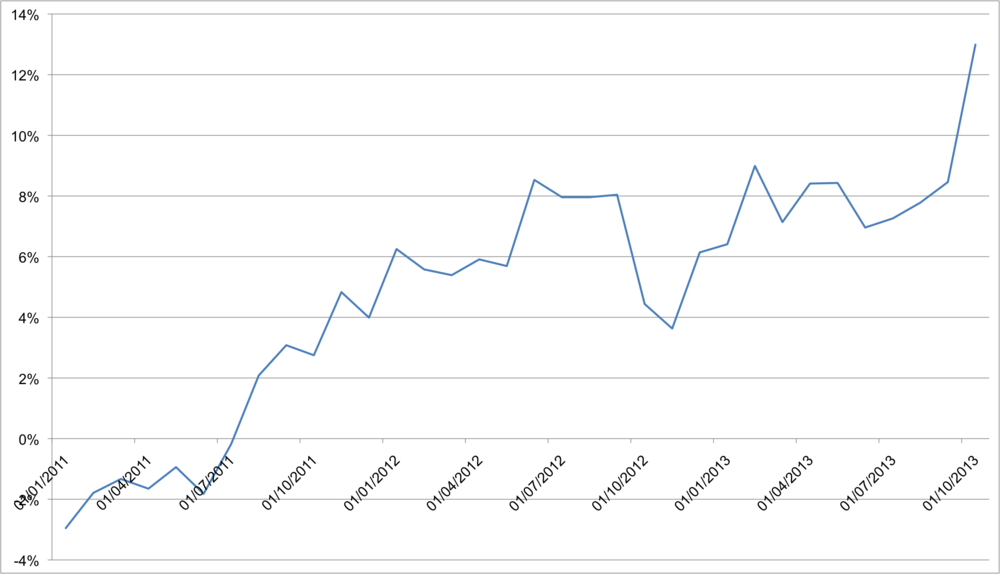

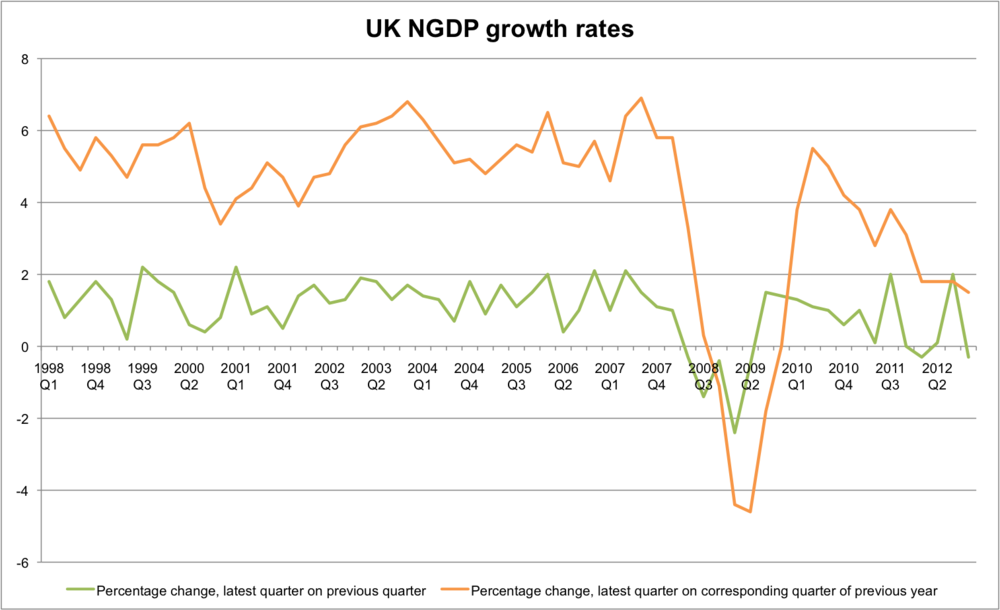

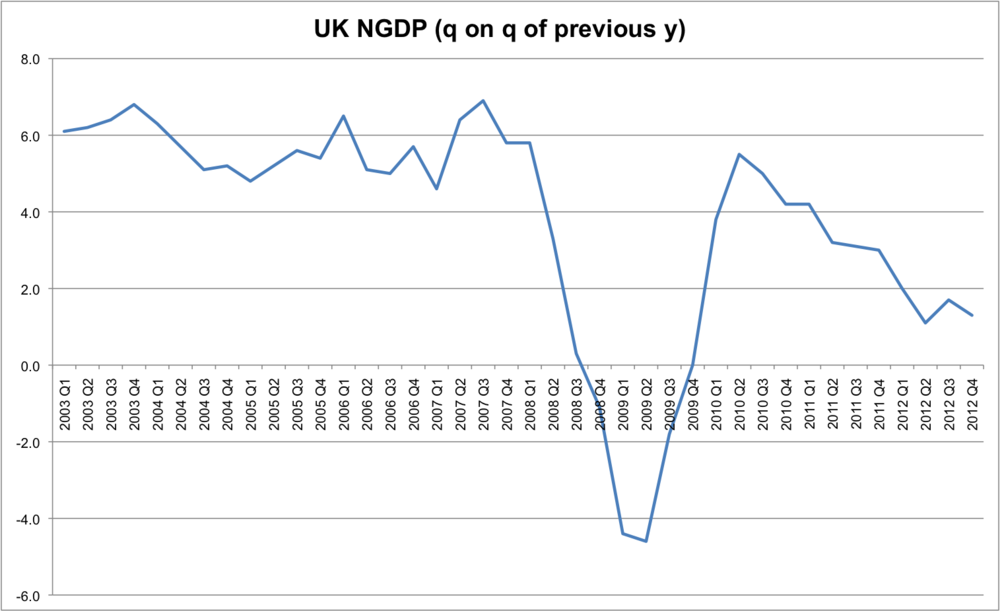

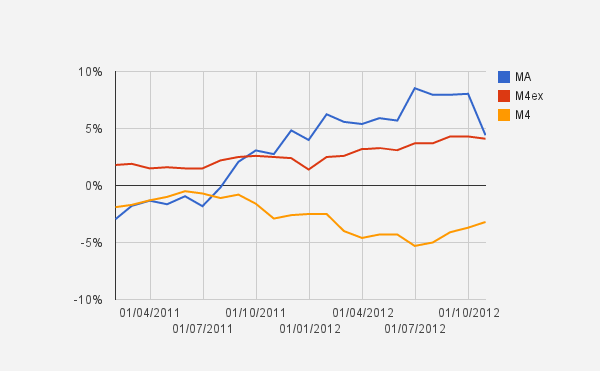

There is a widespread discussion about GDP growth and we want to tap into that. If you ask someone what's happening to GDP they're not going to be thinking in terms of levels (relative to 2009, or some other base year) or indeed the absolute amount. It's growth rates that are in the news. So the real decision is which growth rate - should we compare it to the previous quarter, or to the same quarter of the previous year? Let's look at the data:

The headline growth rate of GDP is in terms of quarter on quarter change, which in our case is the green line. The orange line shows the percentage change based on the same quarter of the previous year. To be clear, the Q4 2012 figure in the chart differs because the green line is relative to Q3 2012, whilst the orange line is relative to Q4 2011. Given how I've argued that we want to tie into the public awareness of growth rates it'd make sense to focus on quarter on quarter change (green). But it's not very interesting. The change relative to corresponding quarter (orange) tells a far richer story, with NGDP growing by around 5% from 1998 - 2007, collapsing to less than -4% in 2009, rebounding in early 2010, and then embarking on a downward trend. Critically this seems a closer fit to thinking in terms of an overall 5% GDP level target. To be sure we're not looking at the level path, so we can't tell from the chart above what NGDP "should" be now in order to get back to the 5% path. But if you want to use 5% as your benchmark you can easily see whether we're "catching up" or "falling behind". And indeed if you advocate a different NGDP level target (for example 2%) then you can still get meaningful insights from a prediction market focused on growth rates.

So we're very much asking a question that is imperfect. But I want to stress that the purpose of the prediction market is to generate interest in NGDP expectations. It is *not* to serve as a policy tool. If you wanted to adopt an NGDP level target you'd need a far richer suite of institutional designs. You'd need the government to release NGDP indexed bonds. You'd need to agree on a level target. Etc. This prediction markets is intended as a very small step to contribute to the wider public debate. So focusing on an annual growth rate is seen as the most modest option. We can't switch debate from real GDP QoQ growth rates to nominal GDP level path relative to an arbitrary growth rate in one step.

The reason we're using the primary release is because this is when there's most public interest in the figure, since it provides the first look. Of course it is likely to be revised in subsequent releases, but it makes sense to only focus on one. In addition the ONS intend to start including NGDP figures in their primary release. We've decided to exploit this happy coincidence.

There are several different ways in which we could ask the question. Previously we used a multiple choice answers to deliver a real time estimate of the probability of each possible outcome. Here were the options:

As it turns out, the second estimate (released February 27th) gave a figure of 109.8. But the third estimate (released March 27th) revised this to 110. The problem isn't just ambiguity about which release would be used, it is because if the "true" value falls close to the border between different options, you lose a significant part of the predictive power. It places a higher burden on the question design (and indeed the question designer!). With that in mind this time the question works in a slightly different way. We set an opening price of £50 and this is scaled by 0.1 to imply an expected growth rate of 5.0%. Traders can either buy or sell shares relating to that probability value, and in doing so move the market.

It remains to be seen whether there's enough interest in this market to warrant a separate one for every quarter. I suspect that we will open up a market for 2015 Q1, for 2016 Q1, etc. We'll respond to market demand. For now though jump in and start trading. If the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee incorporate the insights of this prediction market as a complement to their current sources of information, decision making would be improved. Indeed if they set a rule by which they would alter make interest rate decisions such that this market stays at 5%, we'd be getting somewhere...