Having begun with such a confident headline, the rest of this post will involve a lot of backpeddling. For many economists (not just Austrians) the Wicksellian rate of interest (or "natural" or "neutral" rate) is of central importance for macroeconomic stability. In fact, one might argue that it isn't merely an indicator of the monetary stance - it is the stance.

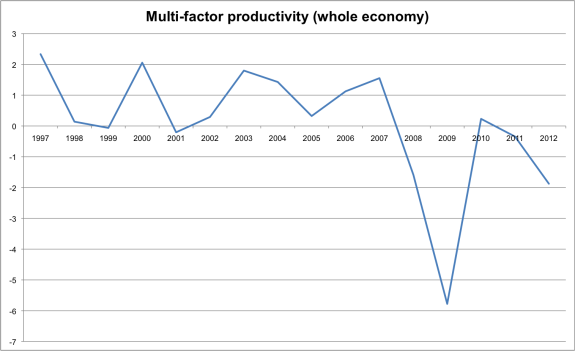

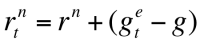

Indeed David Beckworth and George Selgin argued this in a 2010 working paper. This morning I thought I'd attempt to make a very rough estimate of what interest rates would be in the UK - if they were at their natural rate. Their method is based on a Ramsey growth model that says that the neutral rate of interest is a function of productivity growth, population growth, and time preference. For simplicity, they focus on the component that is likely to be most volatile - productivity. Their equation for their estimate of the neutral rate is as follows:

In other words, the neutral rate today is equal to the long run steady real interest rate, plus the difference between expected Total Factor Productivity Growth, and the long run average TFP growth rate.

In other words, the neutral rate today is equal to the long run steady real interest rate, plus the difference between expected Total Factor Productivity Growth, and the long run average TFP growth rate.

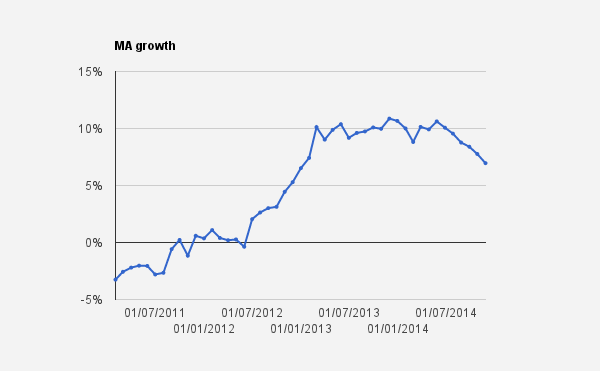

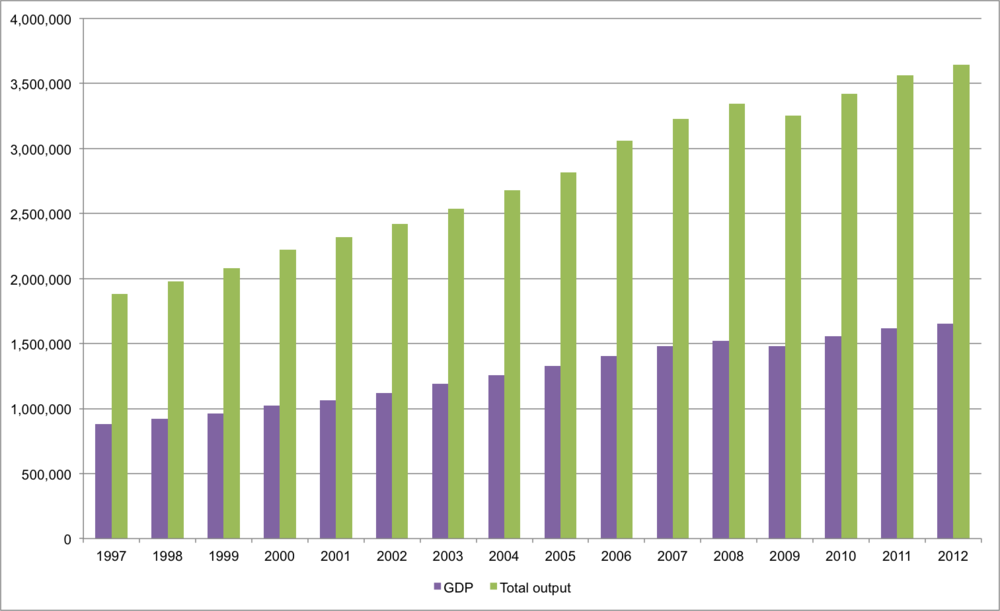

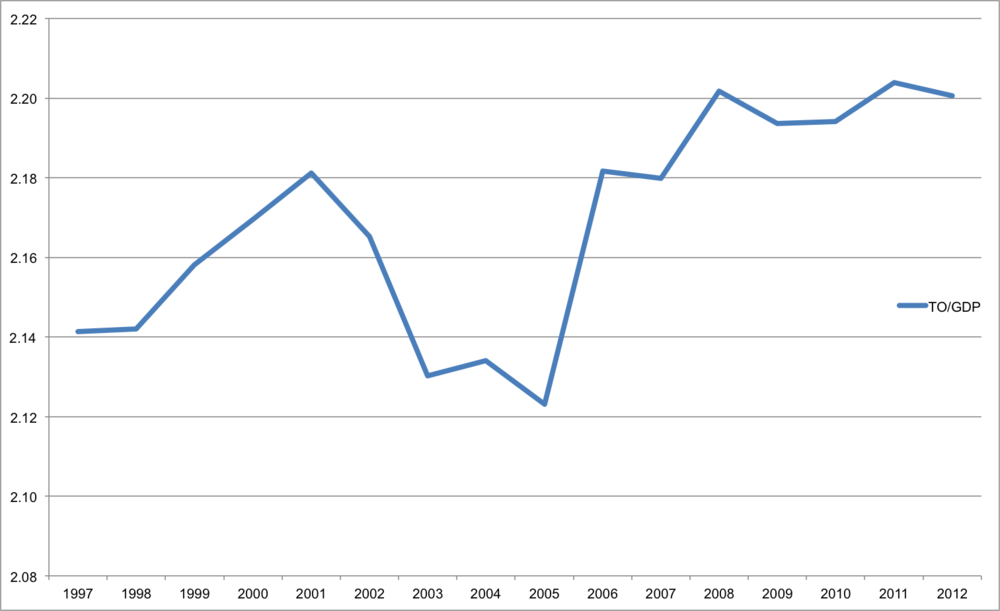

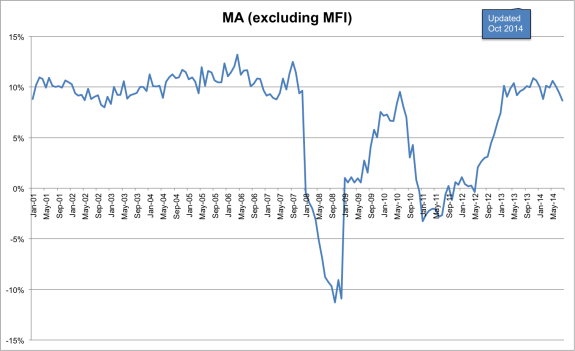

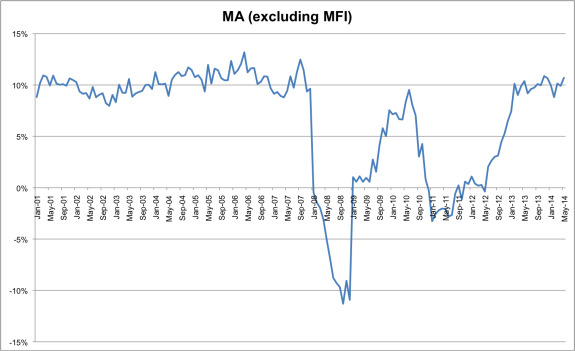

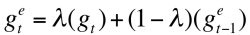

Following them, I assume that the long run steady real interest rate is 2%. For the productivity figures I used the quarter on quarter growth rate of output per worker (series code A4Y0). I then calculated expected TFP using the following approximation of an exponentially weighted moving average:

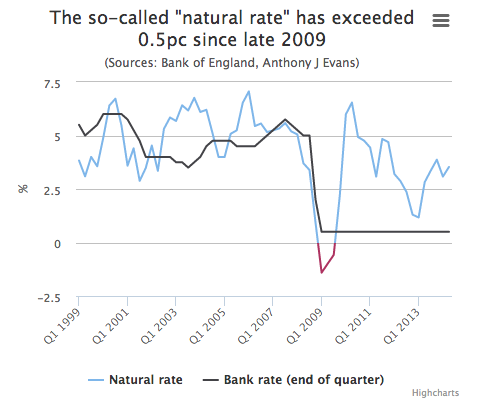

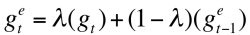

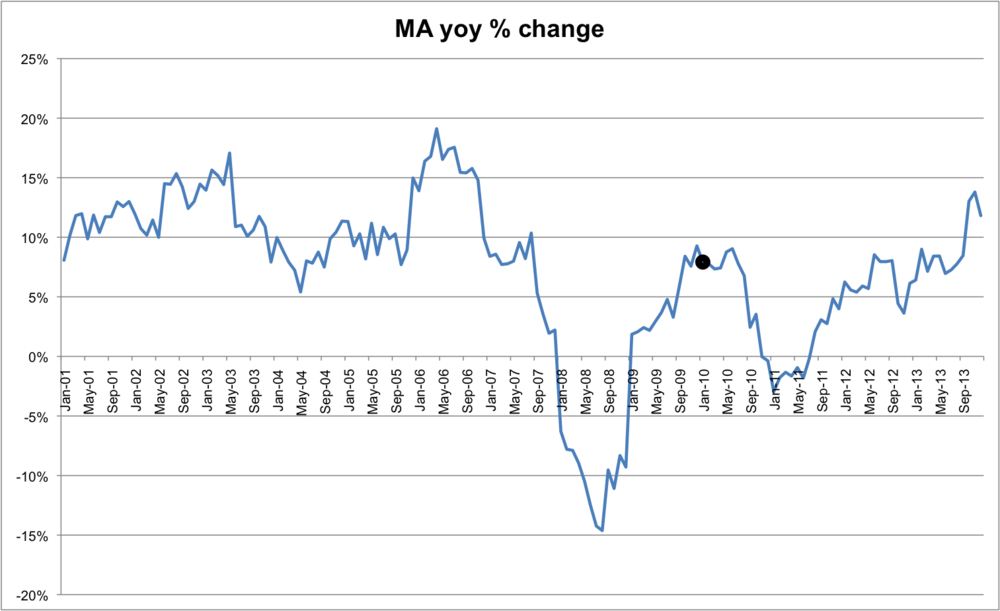

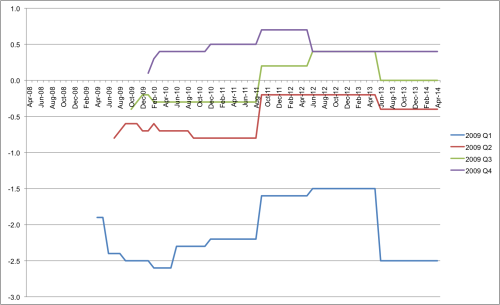

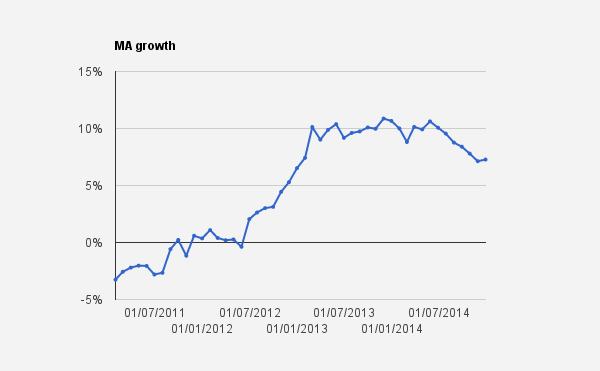

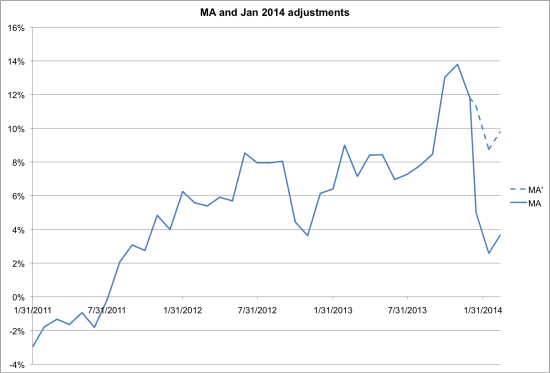

Again, following Beckworth and Selgin I set the coefficient at 0.7. The output is as follows:

Again, following Beckworth and Selgin I set the coefficient at 0.7. The output is as follows:

Once I've had a think about possible errors I've made, and corrected them, I will add this to the data section of the Kaleidic website, and update it regularly. I think the chart broadly fits with intuition - fluctuation between 2%-3% prior to 2008, and then crashing into negative territory. Post crisis the rate is noticebly lower than before, with the latest estimate (Q4 2013) at 1.8%

We cannot observe the real neutral interest rate. But we do know that the long run average should roughly equal any actual long run value, and we do know something about the underlying determinants. I think Beckworth and Selgin have made an important contribution. A few discussion points to bear in mind:

- I've not factored any population changes in, but an increase in working age population should increase our estimate.

- I used quarter on quarter growth rates because they lead to less volatile results but Beckworth and Selgin use year on year rates

- This estimate is a real rate, so shouldn't be compared to a nominal policy rate without correcting the latter for inflation.

- Beckworth and Selgin are obviously comparing this to a real Federal funds rate in order to get a measure of the monetary stance. The Bank of England's Bank rate isn't the same thing as the Federal funds rate, however, so it might be better to compare the estimate of the natural rate with an overnight interbank measure for the UK.