Perhaps not, given that no major central bank has adopted an explicit nominal income (or NGDP) target. However…

I recently spent a very pleasant train journey to Turin catching up on various podcasts. This included several episodes of Macro Musings (the best monetary economics podcast by far, and one that I highly recommend), including:

And I also noticed that Scott was talking about his new book, ‘The Money Illusion’, with Larry White on the Hayek Program podcast:

First off, I found the contrast between the practitioners vs. academics to be fascinating. I’ve learnt so much from George, Larry and Scott and consider them to be three of the most important monetary economists around. I sometimes disagree on points of emphasis, but can’t say that I ever consider their arguments to be flawed. And yet the actual implication of their work is so opposed to the reality of how central banks behave! Perhaps there’s also some context with my recent review of Mervyn King’s ‘Radical Uncertainty’, which frustrated me greatly. There’s something about central bankers downplaying the formalism of the discipline, giving attention to concepts like uncertainty or subjectivism, once they’ve finished their term, that rankles. Carney is so smooth, so confident in his analysis and reflections. And I do think his tenure was a (qualified) success. But he seems oblivious to the depth of insight that free bankers/market monetarists provide. Megan Greene is also an impressive expert, but sidesteps any consideration of public choice, mission creep, or the knowledge problem to present a confident vision of a more powerful central bank. They both provide clarity, and optimism. And I believe that knee jerk critiques are ill founded (clearly there’s scope for central banks to pay attention to climate change within their existing mandate). But just imagine the world we’d live in if Selgin, White and Sumner had the legitimacy and authority conferred by high office …

I haven’t yet read ‘The Money Illusion’ and although I intend to, I suspect I’m familiar with the key points. In terms of these interviews, here are some good points that Scott made, across both of those podcasts, that I hadn’t fully considered before now:

The Fed is usually operating behind the curve. In other words, the natural rate moves faster than their response. That being the case, cutting interest rates are more likely to indicate tight policy than loose policy and raising rates will coincide with loose monetary conditions. More recently, there’s evidence that the Fed are more forward looking, and this implies a major improvement in policy.

The natural rate of interest (R*) can move quickly in a crisis. I’d add that this is in large part because central bank incompetence affects it. This is the “supplier induced demand” argument I made in the chapter of ‘Getting the Measure of Money’ relating to velocity shocks.

Advocates of fiscal policy can be unclear on how they define and use the term ‘liquidity trap’. If it simply means that interest rates are low, and that there’s high demand for base money, then it does indeed exist. But there’s nothing about this situation that implies monetary policy has become ineffective. The issue is whether policymakers have sufficient credibility to use the monetary policy tools necessary to raise nominal growth expectations. Some commentators may favour fiscal policy because they don’t believe that (typically) conservative central bankers will do “whatever it takes”. But the optimal strategy is to hire central bankers that know how to do their job.

Scott argued that we shouldn’t expect central banks to be able to forecast recessions because if we can predict them, we can prevent them. As he has shown us, however, events in 2008 demonstrate that central banks don’t always prevent demand side recessions. Therefore, in trying to predict a recession, we are really trying to predict central bank incompetence.

Despite being an Austrian-school economist I don’t like to use the term “bubble”, and try not to violate EMH. I do think we can talk about “booms” (as in the manifestation of loose monetary policy), and about the difference between primary (Austrian) and secondary (Monetarist) recessions. But Scott argued that many “bubbles” can be plausibly explained by fundamentals:

The 1990s stock market (especially Nasdaq) only made sense of US tech firms would come to dominate the global economy - they did!

The 2000s housing market only made sense if we would be able to rely on very low interest rates and NIMBY restrictions on new housing construction to generate a secular rise in house prices - which is exactly what happened!

What I found most interesting was Scott’s optimistic take on the influence of NGDP targets. He made a few key points:

A flexible average inflation target is one way to permit NGDP playing a role without the embarrassment of abandoning an inflation target.

The Fed’s decision to cut interest rates in 2019, despite inflation being high, indicates an increased concern for market expectations (see falling inflation expectations here) and a triumph of market monetarism.

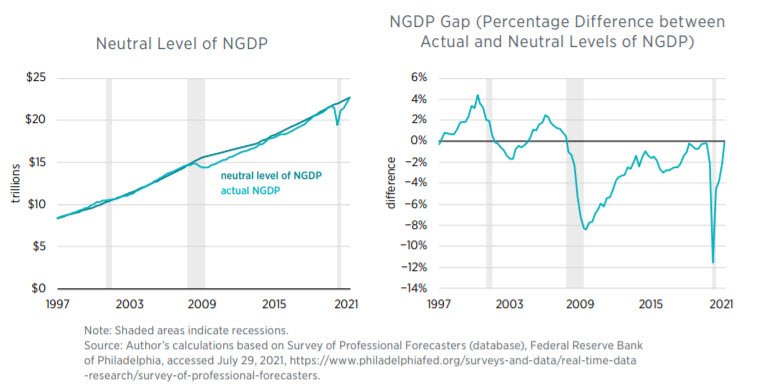

We’ve now got back to the pre-covid NGDP trendline (see David Beckworth’s charts, shown below) which is why this recession hasn’t prompted a debt crisis.

This, in the context with being attributed as “the blogger who saved the economy”, due to the influence he had over the Fed’s late 2012 QE3 program, is a cool achievement. Scott deserves this recognition, and he’s a hero.

My own take, however, is a bit more pessimistic:

Scott emphasises that it’s the level targeting he’s really interested in, not NGDP per se. In which case it might have been a strategic error to focus so much on NGDP when other economists were advocating price level targets (see Chapter 1). Personally, I want to move away from giving consumer prices such an important role in policy decisions and so I’m wary of pinning too much hope on level targets per se.

Although an average inflation target approximates a level target over a suitable time horizon, it provides much more discretion and relies on better decision making than if it were a clearly defined rule (i.e. an explicit level target). There is now a lot of uncertainty about time horizons and too much flexibility is a bad thing for monetary policy. I’m worried that the Fed won’t be able to handle this additional epistermic burden.

It’s clear that Nominal GDP data is too lagged, flawed, and large scale (released quarterly) to provide a meaningful guide for covid related policy. Scott said that we should only be looking 1-2 years ahead and that there’s no point to maintain NGDP on a month to month basis. But this presents a curious problem. One of the main advantages of an NGDP target over inflation targets is the fact that they deal better with supply shocks. If covid is interpreted as a supply shock, but can’t use NGDP data, then we’re really not contributing to the public debate. (This is why I have been using Average Weekly Earnings as a measure of nominal income rather than NGDP, but I don’t advocate using it as a policy target).

Regarding covid, Scott’s attention seems to be more on unemployment data than inflation data and seeing in the former real problems associated with health risks. In this situation, stimulating normal incomes won’t help much because although it would create inflation it wouldn’t provide the nominal receipts required to prevent the downsizing that occurs in a traditional recession. He therefore thinks it’s ok to let NGDP contract sharply, provided there’s a commitment to get back to the previous trend path over a reasonable time period.

Scott considers it to have been a massive unanticipated real shock that monetary policy shouldn’t be expected to do anything about. But if that’s the case it should put upward pressure in inflation. In the UK, inflation didn’t exceed 1% throughout 2020 and has jumped from 2.1% in May 2021 to 4.2% in October. This implies two things to me:

There’s been a lag, and the inflation has only showed up in the data following the reopening of the economy (and the interplay between Brexit and covid re supply chain disruptions). Or

The immediate impact of covid was an unusual demand side recession caused not by a fall in confidence (the typical Keynesian explanation) but by a government mandated fall in spending.

When we entered the first lockdown and saw widespread mothballing my inner Austrian was warning against an assumption of a quick recovery because I felt people were underestimating the intricacies of the supply chain and the capital disruption that would occur. Keynesian appeals to hysteresis can be complementary to Austrian attention to capital heterogeneity (which tells us that recessions take time to correct and cause real damage). However, Aggregate Demand clearly fell in 2020.

Even if you treat 2020 as a demand “problem” it still doesn’t imply that monetary policy was wrong. Imagine that a nuclear superpower invades a sovereign European nation, drawing the US and UK into a third world war. The UK government dramatically ramps up military spending such that measured GDP grows. In such as a case, we would prioritise winning the war over ensuring stable nominal income growth and a temporary boom may be a necessary side effect. Perhaps a similar argument can be made regarding covid - that it’s not a failure of NGDP targets to ignore them in extreme circumstances, and that such instances necessitate government to do more. I don’t think we have the state capacity for government spending to (temporarily) offset the reductions in private sector activity during lock down, so we just put this down to force majeure.

***

When I sat on the IEA’s ‘Shadow Monetary Policy Committee” I struggled to find the balance between interpreting the brief as “what I would do given the remit and constraints faced by central bankers” and “what I’d like to do if I were in charge”. Therefore, I was fascinated to learn that Mark Carney himself admitted to (partially) neglecting the inflation target in order to follow the implications of an NGDP level target. He said that Osborne’s letter (e.g. here, from 2015) that reminded him if the flexibility over time scale gave him the scope to see through some types of temporary deviations from target. What’s really telling, however, is that this is subtle, and being revealed now. But the outcome is clear, and was suspected - if you look at q-on-q4 growth of NGDP from 2010 (with Carney's tenure starting around the orange line) you do see better performance, with 4% NGDP growth +/- 1%.

So, let me close by quoting Carney’s parting words to David Beckworth:

I hope we get your nominal GDP target some day

Some may argue, we no longer need it.